Flywheel is a simple broker for secure pub/sub message streaming over WebSockets. It can run as a standalone cluster or embedded into an existing application. It's easy to extend and supports custom auth'n/auth'z plugins for controlling exactly what your subscribers get access to.

With the already excellent MQTT we're spoiled for choice when it comes to high-speed, low-latency messaging with high fan-in/out topologies. And then you have SaaS-based solutions such as Amazon's IoT. So why Flywheel?

These solutions work well when the client controls what data they wish to receive. If you need to enforce control at the broker level, you're after authorization. This is where things get really complicated, really fast. MQTT, AWS IoT and others allow you to define static auth'z policies, specifying up-front which devices can access which topics (usually through some sort of ACLs and pattern matching). If you can't control how end-users map to physical devices, or if you have to re-evaluate an end-user's privileges at an arbitrary point in time (for example, when allowing for initially anonymous connections that can optionally authenticate later to gain more subscriptions), you're out of luck.

Flywheel auth'z model is dynamic, allowing you to define the behaviour by writing a little bit of code. This gives the broker control over when the security policy is evaluated and gives the client the ability to present their credentials in a variety of ways. Flywheel has equivalents for HTTP Basic Auth and Bearer Auth, supporting anything from a basic username/password combo to JWT tokens, Kerberos tickets, and so on.

If you've used MQTT before, you're probably used to dealing with 3rd party client libraries and pushing bytes around, even though most of IoT-style messaging tends to revolve around simple, concise text strings. And if you need to use HTTP(S), then most brokers will simply tunnel MQTT over WebSockets anyway. So why not use WebSockets directly?

This is exactly what Flywheel does. Using WebSockets preserves natural compatibility with HTTP(S) infrastructure while gaining the efficiency of the WebSocket protocol - full-duplex messaging with only two bytes of overhead per frame. Dispensing with a heavyweight binary protocol gives you the flexibility of using any WebSocket-compatible client, be it the HTML5 WebSocket object native to most browsers, or an equivalent API in mobile devices. The point is that just about every device today supports WebSockets, and it makes for an excellent message streaming protocol. If you need the efficiency of binary messaging, WebSockets support that too, and so Flywheel gives you the ability to publish in both text and binary format natively, without resorting to base-64.

Flywheel builds on MQTT's topic-based subscription model and is syntactically compatible with MQTT topics. Applications utilising MQTT messaging can be ported to Flywheel with no changes to the topic hierarchy and subscription filters. So if you know MQTT, you'll feel at home with Flywheel.

Flywheel can run in either embedded or standalone mode. In embedded mode, the Flywheel broker runs in-process, letting you add message streaming support to a single JVM-based application in a couple of minutes - just import the library and add a few lines of code to configure and start the server.

Standalone mode is used to run one or more dedicated clusters of broker nodes to enable a message streaming capability for an entire organisation, with multiple message publishers and subscribers.

Flywheel was born out of a need for proper configurability and extensibility, particularly in the area of subscription control. It is built around a modular design, and supports two kinds of extension points:

- Auth modules: apply custom auth'n and auth'z behaviour at any point in the topic hierarchy. Multiple auth modules can co-exist, allowing you to apply a different policy depending on the topic.

- Plugins: a general purpose extension, hosting custom code within the broker without altering the broker implementation. Plugins can be used to enhance the capabilities of the broker, for example, adding metrics and monitoring support.

Flywheel is built on an active-active, scale-out architecture, utilising multiple stateless broker nodes to achieve very high throughput over a large number of connections. It's architected around the cloud, favouring containerised deployments, immutability and PaaS. It's efficient too, utilising asynchronous I/O it can accommodate between 10K-100K connections on a single broker node (depending on the H/W specs). Message routing is fully parallel, utilising all available CPU cores.

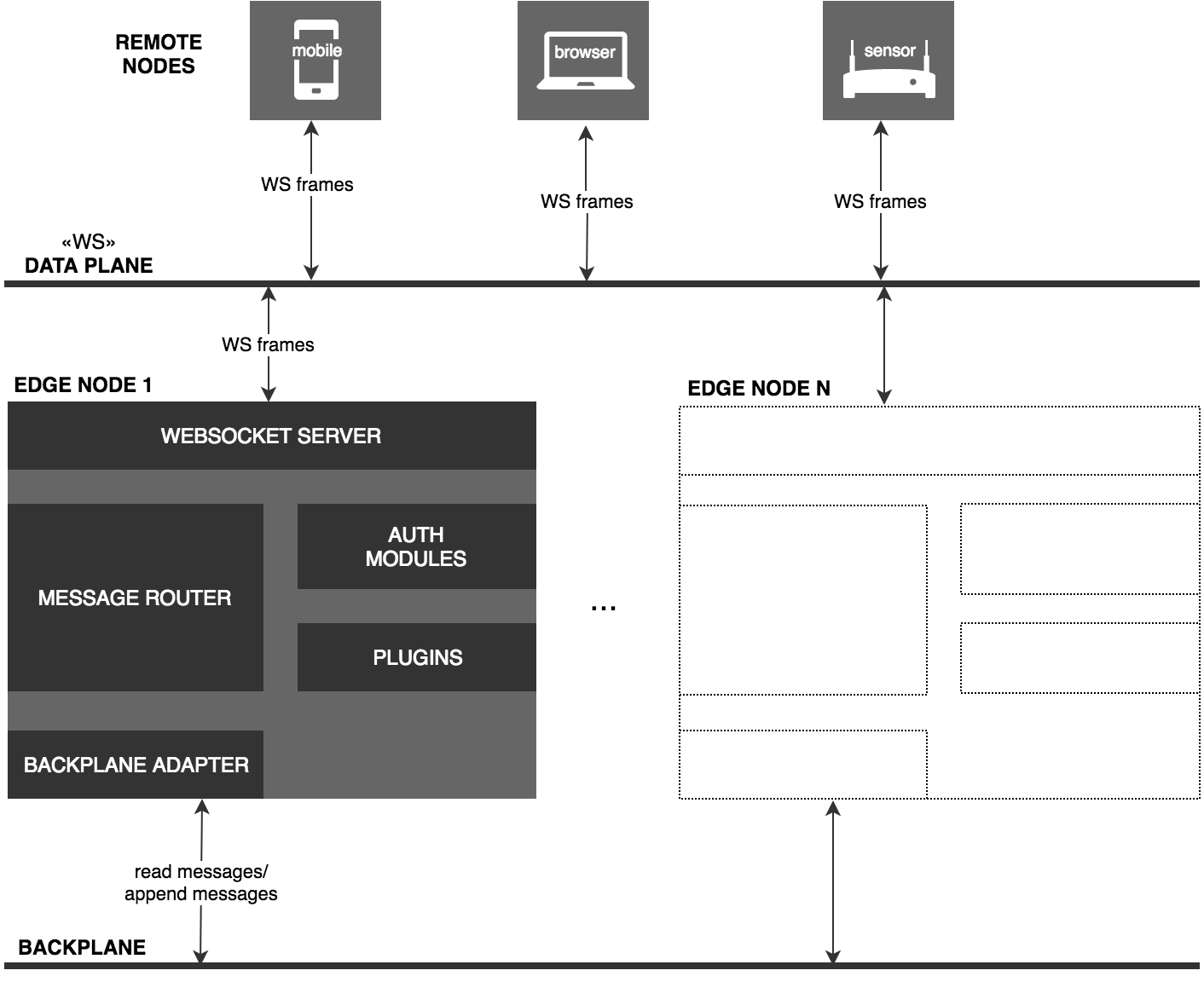

Some brief terminology first.

- Remote Node - A client of the broker that can publish messages and receive messages (the latter requiring a prior subscription to one or more topics). The remote node may connect to any Edge Node in a broker cluster via a WebSocket connection.

- Edge Node - A single broker instance that can be deployed in a centralised cluster (close to its peer edge nodes) or in geographically distributed locations (close to the remote nodes).

- Backplane - A high throughput interconnect between the edge nodes, making messages uniformly available to all edge nodes in a cluster, irrespective of which edge node they were published to.

- Nexus - A single connection between a remote node and an edge node.

The diagram below describes a typical Flywheel topology.

A backplane is an optional component, required only if running Flywheel in clustered mode (i.e. with more than one edge node). Currently, Flywheel supports Kafka as a backplane. For more information, see the Kafka Backplane README.

The first step is deciding on which of the two modes - embedded or standalone - is best-suited to your messaging scenario.

In this example we'll start an edge node on port 8080, serving a WebSocket on path /broker.

Builds are hosted on JCenter. Just add the following snippet to your build file, replacing the version placeholder x.y.z with the version shown on the Download badge at the top of this README.

For Maven:

<dependency>

<groupId>au.com.williamhill.flywheel</groupId>

<artifactId>flywheel-core</artifactId>

<version>x.y.z</version>

<type>pom</type>

</dependency>For Gradle:

compile 'au.com.williamhill.flywheel:flywheel-core:x.y.z'EdgeNode.builder()

.withServerConfig(new XServerConfig()

.withPath("/broker")

.withPort(8080))

.build();That's all there is to it. You should now have a WebSocket broker listening on ws://localhost:8080/broker. Try it out with this sample WebSocket client. It should say 'CONNECTED', and not much else at this stage.

The above snippet will return an instance of EdgeNode, which you can use to publish messages directly. Simply call one of EdgeNode.publish(String topic, String payload) or EdgeNode.publish(String topic, byte[] payload) to publish a text or binary message respectively on the given topic.

Listening to connection states as well as published messages can be done by providing a TopicListener implementation:

edge.addTopicListener(new TopicListener() {

@Override public void onOpen(EdgeNexus nexus) {}

@Override public void onClose(EdgeNexus nexus) {}

@Override public void onBind(EdgeNexus nexus, BindFrame bind, BindResponseFrame bindRes) {}

@Override public void onPublish(EdgeNexus nexus, PublishTextFrame pub) {}

@Override public void onPublish(EdgeNexus nexus, PublishBinaryFrame pub) {}

});If you only care about one or two specific event types, use a composable TopicLambdaListener, feeding it just the necessary Lambda expressions, in the form:

edge.addTopicListener(new TopicLambdaListener()

.onOpen(nexus -> {})

.onClose(nexus -> {})

.onBind((nexus, bind, bindRes) -> {})

.onPublishText((nexus, pub) -> {})

.onPublishBinary((nexus, pub) -> {}));Alternatively, you can you can subclass TopicLambdaListener directly, overriding just the methods you need.

The standalone set-up is considerably more involved than what can be described in a quick-start guide. We recommend reading the standalone module README for a much more comprehensive guide.

We're going to assume that you'll be running the official Dockerhub image and already have Docker installed. Run the following command to download and launch the image in interactive mode.

docker run -p 8080:8080 -it whcom/flywheelThe WebSocket broker will be available on ws://localhost:8080/broker. The image also publishes a health check endpoint on http://localhost:8080/health - useful for running behind a gateway or a load balancer.

The next logical step is to connect to our broker to publish messages and subscribe to message topics. This requires a basic understanding of the Flywheel wire protocol, which comes in two variants - text and binary. As we're just getting started, let's keep it simple and stick to text.

Flywheel adds a lightweight frame structure on top of the basic WebSocket text and binary frames. The text protocol has only three frame types. Every frame starts with a single character - upper-case B, P or R, depending on the frame type, followed by a single space character (0x20). The rest of the payload is specific to the frame type and is an UTF-8 string, as per the WebSocket standard for encoding text frames.

This is typically the first frame sent by the remote node to the edge after opening the nexus, disclosing information about itself and indicating which topic(s) to subscribe to. A bind frame may also contain an auth section, attesting its identity. A bind frame can be sent at any point in time, multiple times if necessary. A remote may send a bind frame each time it wishes to change its subscription, or simply to refresh its security credentials, particularly when using short-lived bearer tokens.

A B-frame has two types of payloads - a request (sent by the remote) and a response (sent by the edge). Below is an example of a bind request frame.

B {

"sessionId": "123456789",

"auth": {

"type": "Bearer",

"token": "8db7752d-7d94-407e-8636-87d912de81b7"

},

"subscribe": [

"quotes/forex/#",

"quotes/shares/AAPL"

],

"unsubscribe": [

"quotes/shares/DELL"

],

"metadata": {

"osType": "Android",

"osVersion": "6.1"

},

"messageId": "123e4567-e89b-12d3-a456-426655440000"

}The request payload must be a valid JSON document with the following fields, all of which are optional:

| Field | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

sessionId |

string |

A remote-supplied identifier, typically a UUID, uniquely identifying the nexus. While a sessionId isn't strictly required, it simplifies the task of matching the remote-end nexus socket to the edge-end socket. |

auth |

object |

Encapsulates the remote's credentials, for access to secured topics - both for publishing and subscribing. The exact schema of the auth object varies with the authentication scheme. See Auth types for more details. |

subscribe |

string[] |

An array of topic filters, indicating additions to the set of subscribed topics for the current session. The topic filter syntax is identical to that of MQTT 3.1.1. |

unsubscribe |

string[] |

An array of topic filters, indicating deletions from the set of subscribed topics for the current session. Note: the unsubscribe topic filters must much exactly the filters used in a prior subscribe; subsets and supersets aren't supported. For example, one cannot subscribe to quotes/shares/AAPL and then later unsubscribe from quotes/shares/# and expect the earlier subscription to be revoked. Again, this behaviour is identical to MQTT. |

metadata |

object |

A schema-less JSON object, providing a free-form conduit for a remote to supply additional parameters during the bind flow. By convention, this data is purely informatory. However, it can also be used to extend the protocol. |

messageId |

string |

Uniquely identifies this message, for correlating the response frame back to the original request. If omitted, an all-zero UUID 00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000 is assumed in its place. |

The two currently supported auth types are Basic and Bearer, semantically equivalent to their HTTP counterparts.

{

"type": "Basic",

"username": "string",

"password": "string"

}{

"type": "Bearer",

"token": "string"

}The following is an example of the response payload.

B {

"type": "BindResponse",

"errors": [

{

"type": "General",

"description": "some-error"

}

],

"messageId": "00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000"

}| Field | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

type |

string |

The string literal BindResponse. |

errors |

object[] |

An array of error objects, populated if one or more aspects of the bind request resulted in an error. See Error types. |

messageId |

string |

The messageId from the request frame, or 00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000 if no messageId was supplied in the request. |

The two currently supported error types General and TopicAccess.

{

"type": "General",

"description": "string"

}{

"type": "TopicAccess",

"description": "string",

"topic": "string"

}A receive frame is sent from the edge node to the remote, typically containing a broadcast message that matches a subscription filter. An edge node may also send an unsolicited direct message to the remote. See Direct messaging for more details on the latter.

The payload of an R-frame comprises two segments, separated by a space character. The first segment corresponds to the topic name. The second segment is the message body.

The following is an example of a receive frame.

R quotes/AAPL {"bid":148.82,"ask":148.84}Note: the message body has no particular structure. In the example above it's a JSON document, but it is really up to your application to define how the body is structured.

A publish frame is sent from the remote node to the edge, containing a message to be delivered to all subscribers with a matching topic filter.

The structure of a P-frame is identical to that of an R-frame; two segments separated by a space. The first - the topic name; the second - the message body, as shown in the example below.

P quotes/AAPL {"bid":148.82,"ask":148.84}Direct messaging allows for discrete communication between the remote and the edge nodes, without incurring a broadcast. The built-in direct messaging scheme uses a topic hierarchy in the form $remote/{sessionId}|anon/rx|tx/.... Let's dissect this.

At the top level we have the special $remote topic container. This topic and all of its subtopics are locked out by default; remotes are not allowed to subscribe to arbitrary topics within the $remote catchment. The next level is either the session ID, if the remote has supplied one in an earlier B-frame, or the literal anon. The next level is from the perspective of the remote node - either the literal rx - if the message is being received by the remote node, or tx if it is being sent by the remote. There may be zero or more additional levels, depending on the type of message.

The most common use case for direct messaging is communicating errors back to the remote node based on an earlier publish that couldn't be processed. Because publishing is purely asynchronous, the publisher wouldn't ordinarily wait for a response; besides, it's very unlikely that a publish operation would fail. But the remote may have attempted to publish on a topic to which it has no access. In this case the edge node will send an array with a single TopicAccess error object back to the remote node, on the topic $remote/{sessionId}|anon/rx/errors.

Note: The above describes the built-in scheme, which is minimalistic by design - initially to accommodate asynchronous error handling. The combination of a flexible topic hierarchy and pluggable auth modules allows you to create secure topics and bespoke routing behaviour, ranging from direct messaging, to P2P, private groups, and so on.

Flywheel was designed to be 'SDK-less'; connecting on any platform supporting WebSockets and with a little bit of string concatenation and parsing based on the ultra-simple protocol, you have a client at your disposal.

Alternatively, you can use one of the existing client libraries. The following snippet shows how it's done in Java.

RemoteNode remote = RemoteNode

.builder()

.withClientConfig(new XClientConfig().withIdleTimeout(300_000))

.build();

RemoteNexus nexus = remote.open(new URI("ws://localhost:8080/broker"), new RemoteNexusHandlerBase() {

@Override public void onText(RemoteNexus nexus, String topic, String payload) {

System.out.println("Text message received: " + payload);

}

});

BindResponseFrame bindRes = nexus.bind(new BindFrame(null, null, null, new String[] { "quotes/#" }, null, null)).get();

System.out.println("Bind response " + bindRes);

nexus.publish(new PublishTextFrame("quotes/AAPL", "160.82"));This is a simple example that opens a single connection to ws://localhost:8080/broker and registers a text message handler. It then binds to all price quotes and prints the bind response. Then we publish a price and receive it back.

By extending RemoteNexusHandlerBase you can subscribe to a range of events.

void onOpen(RemoteNexus nexus);

void onClose(RemoteNexus nexus);

void onText(RemoteNexus nexus, String topic, String payload);

void onBinary(RemoteNexus nexus, String topic, byte[] payload);- Standalone - Building, configuring and running a Flywheel instance using Docker or directly from the command line.

- Kafka backplane - Setting up a Flywheel cluster using a Kafka backplane.

- Remote SDK for JavaScript - SDK for HTML5 compliant web browsers, wrapping a stock

WebSocketAPI.