IS579 Fall 2023

https://github.com/mhouser42/Invasive_Species_Propogation

Justin Tung: https://github.com/JayTongue Matt Adam-Houser: https://github.com/mhouser42

preprocessing.py- Cleans and processes data from outside sources and transfroms into csvs for later use.my_classes.py- Two custom classes for network construction and simulation: ACountyclass with static attributes related to geographic, population, Tree of Heaven (ToH) and regular tree densities for counties, and dynamic attributes related to SLF population and spread. And aMonthQueueclass used in the life cycle simulation.illinois_network.py- Constructs NetworkX Graph of Illinois counties, pickling graph and handlers for further use.run_simulation.py- Simulates the invasive spread of the SLF through Illinois, either on annual or month timeframe. Inputs parameters for run mode and how long to run the simulation for. Uses an accumulated dataframe that inserts rows based on each successive year the simulation is run.visualization_functions.py- Collection of fuctions used in Jupyter Notebooks to visualize the spread of the Lanterfly.visualize_simulation_results.ipynb- Visualizes the baseline spread of SLF, as well as population-based, quarantine, and poisoning ToH counter-measures. Plots aggregate saturation for specified number of simulation runs.life_cycle.ipynb- Variation ofvisualize_simulation_resultswhich operates on a monthly basis and utilizes class methods to flucuate adult SLF and eggmass populations.

locationfolder - Contains NetworkX graph and handlers, as well as csvs for network constructionlydefolder - Contains data from lydemapr project. Unused aside from heuristic reference.treefolder - Data obtained from EDDmaps related to ToH sightings.coef_dict.JSON- Json file which inserts startingsaturation,slf_pop, andegg_popinto each county.

The Spotted Lanternfly (SLF) (Lycorma delicatula) is an invasive species originating from China, Bangladesh, and Vietnam. It was accidentally introduced to North America in 2014, first detected in Pennsylvania before eventually spreading to 14 other states. The SLF is very problematic due to its consumption of plant life, both endemic and agricultural. Its droppings also encourage mold growth, further detrimentally impacting the host plant (University of Illinois Extension "Spotted Lanternfly Fact Sheet").

On September 16th of this year (2023), it has been spotted in Illinois for the first time (Illinois Department of Agriculture). The University of Illinois has warned that the SLF could potentially devastate grape and logging industries, causing a total of $50.1 million annually.(PennState College of Agricultural Sciences "Assessing Economic Impact").

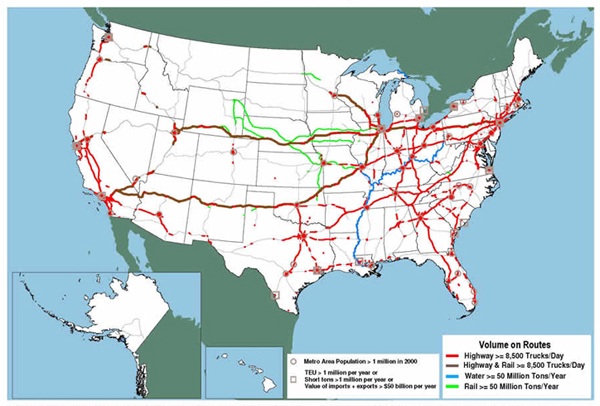

While the SLF has a relatively short range by flight, it often travels long distances when they or their eggs are carried by vehicles, shipping containers, or any other vector. The image on the left shows a hypothetical spread of the SLF across the United States, and the image on the right shows a network of major highways.

| Spread of Spotted Lanternfly | Major U.S. Highways |

|---|---|

|

|

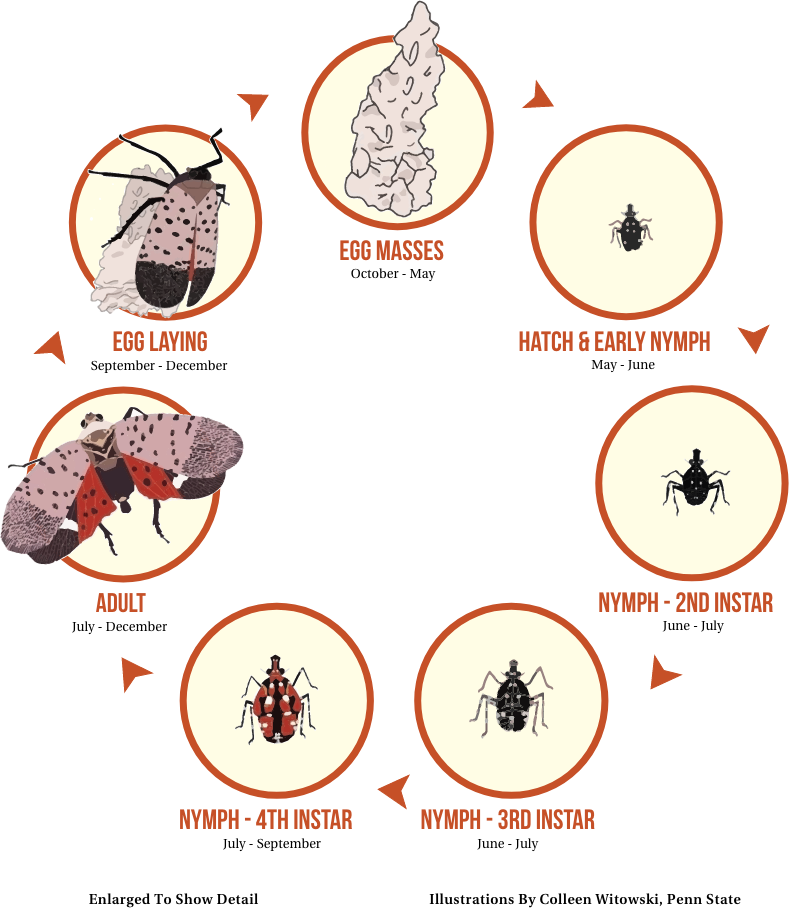

The SLF life cycle is characterized by adults mating, laying eggs, dying off in the winter while eggmasses survive, before hatching in the spring (John B. Ward & Co.).

The SLF also has a unique interaction with an invasive tree, the Tree-of-Heaven (ToH) (Ailanthus altissima). This Tree comes from China and Taiwan and was introduced to the United States in the late 1700’s because of a rapid growth speed, toleration of poor air and soil, and ornamental qualities (Penn State Extension, "Tree of Heaven"). However, this tree soon fell out of favor because of its prolific root sprouting, foul odor, and weak wood (Penn State Extension "What Should You Do with Spotted Lanternfly Egg Masses"). The Tree-of-Heaven is the SLF’s preferred host.

The purpose of our Monte Carlo is to simulate the spread of the lanternfly and explore potential preventative measures.

Two primary datasets provided the data for this model The first is aggregate data from US locations compiled by Sebastiano De Bona et al. in their 2023 paper “lydemapr: an R package to track the spread of the invasive Spotted Lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula, White 1845) (Hemiptera, Fulgoridae) in the United States.” The data from this research paper is available on GitHub. The second is data compiled by Cornell University’s New York State Integrated Pest Management Program. Their map is frequently updated and freely available online.

For construction of the nodes, data on county boarders was obtained via Wikipedia. Additional information was collected on Tree of Heaven was collected from the website EDDmaps. This data is recorded sightings of the plant. Once sighted, experts will review the record and confirm if the sighting is authentic. Data from Illinois was separated out, and an aggregate of sightings from the last five years were added to our model. Information on the Illinois Tree Density was also used from the 2015 US Forrest Service Resource Bulletin of Illinois Forrests.

We ran two seperate simulations, a primary model on a annual basis, and another on a monthly basis which incorparated the SLF life cycle. Many deterministic variables are the same between the simulations, but the probalistic models differ. Differences in design and outcomes will be outlined below.

In researching mathematical models of ecological phenomena, we quickly encountered two primary challenges. Firstly, many of these models are much more mathematically complex than we could effectively do or learn to do in the assignment period. Secondly, many of these models evaluated a lot more information than we were specifically able to find about the SLF.

Given this, we did our best to focus on a smaller selection of key variables. Instead of following an initial idea of modeling individual entities such as flies, wasps, trees, etc., we decided to relegate our abstractions to percents. For instance, a key variable, infestation rate, is indicated as a percentage, where 100% infestation means the maximum amount of SLF that the ecology can sustain. This allowed us to constrain our variables to appropriate ranges that could still meaningfully represent the concrete reality the variables are intended to capture. Other variables we consider this way are the ToH density of each county, which is similarly a percentage.

There are also several concrete variables we consider. For instance, the population density of each county, each county’s geometry, and each county’s centroid.

Another aspect of our test design was to represent counties as nodes in a network. After finding the counties adjacent to each county, we represented these borders as edges, since they would be natural corridors for the SLF to spread. We also represented spread via major roadways by incorporating additional edges along these roadways to represent a vehicle-based spread. While a more comprehensive project may consider more natural barriers, the length and speed limit of road edges rather than their mere existence, for the sake of simplicity, the only distinction we make between edges is if the counties are connected by an interstate.

The probabilities we used were tailored to each randomized variable. Each month, the intrinsic growth of a county’s infestation rate as well as the chance of infestation from each of the county’s neighbors is calculated to change the county’s new infestation rate. The chance of an infestation growing intrinsically is modeled by a normal distribution with a mean of 0.025 and a standard deviation of 0.01. The probability of neighboring influence from each county is modeled by a normal distribution with a mean of 0.5 and a standard deviation of 0.8.

The ToH is given a randomized chance to increase the infection rate due to its influence on SLF propagation. This probability is modeled with an exponential distribution with a scale of 0.02. Since the ToH is also a limited resource that SLF can deplete, and cannot host all SLF beyond a certain point, an exponential distribution seemed the most appropriate. The benefit to SLF would be great if they are in smaller number, but quickly diminishes as the ToH becomes saturated and depleted.

For population interventions, we modeled this effect with a normal with a mean of 0.3 and standard distribution of 0.1. The normal distribution here felt the most appropriate as a representation of human decision-making. This population will probably have some people who intervene a lot, and some people who intervene a little, and a median that is on neither extreme where most people sit.

For quarantine measures, we let the decision to quarantine be 50/50. Since this comes down largely to a matter of governance and public policy, any predictive or behaviorally normative model is likely going to be flawed. Rather than try to develop such a model by doing time-intensive historical research on quarantine-related countermeasures enacted by different jurisdictions that may be relevant to this study, this probability was left as a random Boolean.

The specifications for the numbers are largely the product of our best estimates. This is because of the difficulty in finding established statistical models for simulating the infestation of an invasive species that was appropriate in data requirements, mathematical complexity, and scope to what would be a successful project. These numbers were also adjusted as the model was developed and refined.

The majority of the numerical values used for this simulation were the result of best-effort estimations and deductions of variables. As mentioned before, established formulas for species propagation were beyond the appropriate scope in terms of complexity and data requirements for us to implement, if the data even exists at all. The existance and availablility of data was also strong contributing reason for the limitations on the design of the simulation. For instance, the Penn. Dept. of Agriculture states that "No efficacy data currently exists for any of the available systemic insecticides" in its discussion on trap trees (Penn. Dept of Ag., "Spotted Lanternfly Property Management").

The numerical values used in our project can be therefore construed in two ways. The first is the result of a best-effort to repeat known results and conform to general realistic understandings of the situation the simulation models. The second is a simulation of a possible intervention. For example, there are a wide variety of ways that an ecologicla quarantine could be implemented by various state and local authorities. The quarantine simuation this model contains is one such possible quarantine model.

Test implementations of the model included a mechanic where one population of SLF would decrease as it infected its neighbors, but a decision was ultimately made not to continue with this route. The reasoning behind this was that since the annual simulation includes a full breeding cycle, if every pair of SLF lays 40 eggs (egg clusters tend to contain 30 to 50 eggs (Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, "Spotted Lanternfly Property Management")) when those eggs hatch, it could replace the two SLF required to make it, infest the one county it is situated in, then provide as many SLF as it had the previous year to 37 other counties. Since no county has even more than 10 adjacent counties, in the scope of a year, one county's level of saturation will not practiaclly decrease by it raising the saturation of neighboring counties.

Small note: this model uses a different edge weight for interstate edges, of 0.25 instead of 0.5, increasing likelyhood of infestation spread along highway networks.

The SLF population is modulated on a monthly basis, with County class methods being triggered on different months, with mate occuring between August - December, lay_eggs occuring between September - November, die_off occuring January and February, and hatch_eggs occuring in May and June. The probabilities for each method are as follows:

mate- a random normal distribution centered around 25% and varying between 15% and 35%. This chance is modified by the current adult SLF population, adding to the total of mated adults.lay_eggs- a random normal distribution centered around 50% and varying between 30% and 70%. This is modified by the number of mated adult SLF, ToH and regular densities, and an extra eggmass chance. Female SLFs usually lay one eggmass per seaason, but approximately 12% lay a second eggmass (Belouard & Behm, 2023). The extra eggmass chance in this model is a normal distribution of 12% with of variance of 4%.die_off- a random uniform distribution of 85% to 100% of the adult lanternfly population.hatch_eggs- a random uniform chance between 75% and 100% that an eggmass will hatch. For each eggmass, there is a random uniform distribution of between 0.035 - 0.045 to represent that each egg mass tends to hatch between 35 - 45 SLF.

After life cycle methods have triggered, the calculation for the spread of infestation occurs. The probability of a infestation spreading from one county is a random normal distribution of 10%, with a variance of 5%. This is modified by the counties current adult lanternfly population, and the combined regular tree and ToH densities for the neighboring county. While it is impossible that a SLF could know what a neighboring county's tree densities are before migrating, this represents the capability of them to establish themselves once they have arrived. Finally, the probaility is modified by the edge weight between counties and the current month's traffic levels.

Once a spread probability has been established, spread_infest then spreads adult lanterflies by that amount modified by a variability of between %5 - 15%. If the current month is during a lay_eggs cycle, this also can spread eggmasses.

Once baseline spread has occured, counter measures are implemented if simulation is configured for a particular run_mode and certain conditions are met. The countermeasures are as follows:

- Population Based - If a county's infestation/saturation has reached 50%, or it is half of a neighboring county's saturation that also has an aware public, it's

public_awarenessis set toTrue. OnceTrue,die_offis triggered each month, at an intially normal distribution of 35% with a variance of 10%, modified by the population density of a county divided by 10000. A similar interaction occurs with that county'segg_popas well. - Quarantine - The quarantine counter is an addition to the Population-Based counter-measure. If a county's saturation reaches over 75%, it will enter a state of quarantine, and also trigger public awareness in all neighboring counties. While in quarantine, the weight of the edges between it and all of it's neighbors raise to a random uniform distribution of between 2 and 5, greatly reducing the spread probability into and out of the county. This state is mostly permanant, only turning off is a county's saturation drops below 10%, in which case, the weights of edges between counties will return to prexisting levels as long as its neighbor is not also in quarantine.

- Poisoning Tree of Heaven - If a county becomes aware of the infestation, a

toh_triggerwill change toTrue. OnceTrue, this value will not revert. Each month after the trigger event,die_offoccurs based on thetoh_densityof a county, divided by a normal distribution of 50 with a variance of 25.

A realistic projection of SLF infestation is very difficult to quantify, and available data and literature from reputable sources supports varying results. For instance, De Bona et al. show a map of the 8 years of spread since introduction to in 2014.

(De Bona et al. 2023)

Howver, Jones et al, in developing a specially and temporally dynamic forecast for SLF infestation, show perhaps a quarter of the United States and being partially or completely innundated with SLF in just 7 years.

(Jones et al. 2022)

Our simulations, especially our baseline simulations, exhibited strong statistical convergence. Even without calculating a precise P-value, a clear trend line is still discernable. The resulting graph of our baseline simulation is very similar to a well-established species invasion model.

(This one is from Lovett et al., but many like it are available)

More confidence was imparted in our simulation and methodology since our graph was reproducing a known statistical behavior, and bears repeated convergence. The outcome of the graph also makes intuitive sense. When an invasive species is relatively new to an area, their population is low and growth will be slow. As the population increases, so does the rate of infestation. However, an inflection point is reached, where the growth begins to slow due to depletion of natural resources such as food and habitat, and the growth increasingly slows as the ecology reaches full saturation.

Because of the nature of ecology, the cost associated with running different experiments is almost comprehensively prohibitive. Once a species has infested an area, their removal is nearly impossible. As such, areas facing infestation really only have one shot to try to get it right and achieve their desired outcomes.

In conducting our research, we came across several different countermeasures against SLF. We decided to include three experimental variables to manipulate and assess outcomes from.

Given the known connections between the ToH and the SLF, many efforts have targeted ToH populations in an area facing SLF infestation. These efforts largely take place in one of two ways. The first is to simply try to eliminate ToH. This is done as all tree removal is done, and is laborious, time and labor intensive, and can be impractical in many situations (Brandywine Conservancy). The second, called the “trap tree” approach, is to treat trees with a systemic insecticide. Doing so doesn’t kill the tree, but will make the tree poisonous to SLFs that will still preferentially seek it out (Penn State Extension "Controlling Tree of Heaven: Why It Matters").

Note that the ToH itself is invasive and ecologically harmful in many ways, so while insecticide may be a good way of counteracting SLF, counteracting the ToH itself may be a priority in many instances. However, this set of priorities is not incorporated into this simulation. Only the trap tree approach is evaluated here.

Implementation of the trap tree approach would effectively not just negate the benefit of the ToH to SLF, but actively harm it. Every SLF which would want to feed and lay eggs on it would instead find itself and its eggs poisoned. While this has the potential to substantially negatively impact the infestation rate, the way our simulation modeled this was to flip change the positive impact of the ToH to a negative one, but otherwise modeling the same probability.

We predicted that this experimental variable would have an effect in depressing the SLF, but a less substantial one. This is because ToH is not as well established in Illinois as it is in some other states where these measures have been taken, such as Pennsylvania.

One common piece of advice given on sites discussing SLF is to report sightings, and moreover, to kill SLF if possible, and look for eggs and kill them, especially if they’re on something like car, which can help the SLF disperse (see e.g., Penn State Extension "What Should You Do with Spotted Lanternfly Egg Masses").

In order to model the efficacy of these population-based countermeasures, we factored in the population density of each county, and used a standard distribution to represent human decision-making. Since some individuals would kill very few SLF or eggs, and some would kill many, we assumed that most would be somewhere in the middle, probably on the lower side. We predicted that this experimental variable would also help to prevent SLF, but a less substantial one. After all, while many counties have a high population density, many counties also have very low population densities. This means that if there are populations of the SLF in those counties where detection is very unlikely, then these can spread rampantly.

Ecological quarantine is always a challenging to implement, given the how long boarders between counties can be. However, quarantines are still often implemented. One prominent model for this is Pennsylvania. Its department of agriculture instructs both residents to follow certain protocols, such as inspecting vehicles, boats, and natural materials such as logs which may get transferred from one area to another. Businesses are given further instructions and are required to have an SLF Permit or to hire companies that have a permit (Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture).

While no quarantine is 100% effective, our model simulates quarantine as if it were. If an infestation rate is over 50% for a given county and a random choice generator picks True, then that county’s infection from neighboring counties is 0. That county’s quarantine then remains in place for the remainder of the simulation.

We predicted that this measure would be the most effective out of all three. First, it is non-discriminatory. Every county has the same chance to meet the required criteria for quarantine. Secondly, knocking a neighbor infection rate to 0 is a substantial mathematical impact on the growth of the infestation rate. These factors all combine to make this countermeasure a powerful one to consider.

The results conformed to expectations in some ways and defied them in others. This is the resulting graph of the three countermeasures, compared to the baseline:

While all three countermeasures had an initial effect of slowing down the infestation of the SLF, the population-based countermeasures depressed the curve initially more than other areas. This is probably because of the areas that had the most SLF introduced were also areas of major commerce and rigorous transportation, which also tend to be areas of higher population density. These measures were then followed by quarantine, then trap trees.

However, comparing the trend lines as well as extending the length of time simulated reveals two interesting things. The first is that at a certain point, the trap trees and population-based countermeasures lines both stop increasing. This is somewhat true for the Quarantine line as well, but the quarantine line travels more asymptotic to the baseline. This simulation has been run out to 100 months and this is still true. Initially I assumed that this was due to some error in the mathematical model. But this may not be the case. The infestation percentage, in our model, is a representation of the maximum population of SLF a given area can sustain. Both trap trees and population-based countermeasures may have effectively changed not just the rate of infestation, but the hospitability of the area to the SLF itself. Stated differently, these two countermeasures changed what 100% infestation means. They made the ecology fundamentally more hostile to the SLF.

The second surprise was that the same did not exist for the quarantine countermeasure. Although it initially depressed the infestation curve pretty well, the line continued to shoot up to where it was nearly identical to the baseline result after a while. But this also makes sense when considering that quarantine in this model only negates the infestation that comes to it from adjacent counties, not growth of the population it already has.

Like Trap Trees and Population-Based Countermeasusures, the All simulations increases further, but steadies at a level lower than all of the others. This makes sense since it's has the combined effects of slowed growth from quarantine, and a permenantly depressed infestation level from Trap Trees and Popoulation-Based Countermeasures.

The Baseline spread of the infestation shows some promise, with accelerated growth along interstate edges. However, the spread of the model is far too fast, with full saturation occuring at year eight. This is, of course, without any counter-measures. Implementation of zero counter-measures would be illogical in a real-life scenerio. That being said, we are erring on the side of caution and assuming the model is faster than it should be.

Intially, the poisoning of ToH is the least effective model. This is most likely a result of the toh_trigger variable. Earlier models did not include this, and the poisoning was much more effective. But since the poisoning now only begins once a county is publically aware of the problem, the SLF population has already been established and isn't as easily reduced. However, due to the slow growth of ToH, overtime the saturation is flattened, and actually begins to trend downwards.

Population Counter-Measures suffered from a problem similar to poisoning the tree of heaven, where it only affected counties with extremely high population density. This effectively results in only Cook County and Sagamon counties and the counties surrounding them area being able to reduce the SLF population enough for it to make an impact.

The most effective counter-measure in this version of the simulation is the quarantine. The previous population based counter-measures, combined with increase the edge weight significantly in counties with high saturation, results in lockdowns occuring before the lanternfly can spread. Quarantine also trigger public awareness in neighboring counties allows them to kill the population before it can permanently establish.

Obviously, the most effective counter measure is the one that combines all approaches. Because of quarantine triggering public awareness in other counties, the poisoning of ToH occurs much sooner than it otherwise would have, this combined with the population-based killing results in an effective erradication of the SLF.

The weakness of these simulations, as acknowledged several times, is the mathematical model. The expertise and resources it would take to model this more comprehensively were overwhelmingly prohibitory. However, despite this, several strong conclusions can still be supported by the outcome of the simulation.

Clearly, any countermeasures are better than an uninhibited spread. However, depending on the priorities of different locales, certain countermeasures may be preferable to others. For instance, the most overall depression in the model was with trap trees, but the highest initial depression was from population-based countermeasures. Quarantine may initially be successful, but may be politically prohibitive. Trap trees requires expertise with identifying and treating trees, which may be too high an educational barrier to implement compared to population-based countermeasures, where residents may be taught to recognize the SLF from a few pictures.

Generally, both models showed a very agressive baseline spread, likely more aggressive than would may occur, but as mentioned earlier, there is no consensus on the speed or aggression of a mitigated or unmitigated spread. Additionally, all simulation outcomes are predictive, and cannot be validated against an actual documented spread in Illinois.

A future work could involve creating a network of Pennsylvania counties in a fashion similar to this one, and adjusting variance and modifiers, ideally to mimic an infection curve as it is documented in real-time. This would be accompanied by more granular data-gathering about the countermeasures employed in Pennsylvania.

Another further expansion of this project could be to explore more variations within each countermeasure. For instance, the quarantine threshold would likely look different if a county was 75% or 25% likely to declare and enforce a quarantine, or if residents of a county were more enthusiastic about finding and killing SLF. Doing this may require a more comprehensive and complex simulation, but it may yield results that can show a more nuanced insight into each of these interventions.

Additionally, a further expansion of the project may be to tweek the monthly and annual simulations so they can compute probabilities and outcomes with higher cohesion. While both models reflect a projection of the invasion with probability, they, at this point, represent different approaches to the same problem. Cohereing the inputs, calculations, mathmatical models, and probabilities in a further expansion may yeild the benefits of both approaches and help give a more accurate prediction.

- APHIS. "Spotted Lanternfly." Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, United States Department of Agriculture, n.d., https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/hungry-pests/the-threat/spotted-lanternfly/spotted-lanternfly.

- Belouard, N., & Behm, J. E. (2023). Multiple paternity in the invasive spotted lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae). Environmental Entomology, 52(5), 949–955. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvad083

- Brandywine Conservancy. "Invasive Species Spotlight: Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) and Spotted Lanternfly." Brandywine Conservancy, n.d., https://www.brandywine.org/conservancy/blog/invasive-species-spotlight-tree-heaven-ailanthus-altissima-and-spotted-lanternfly.

- Cornell University, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. "Spotted Lanternfly Reported Distribution Map." New York State Integrated Pest Management, n.d., https://cals.cornell.edu/new-york-state-integrated-pest-management/outreach-education/whats-bugging-you/spotted-lanternfly/spotted-lanternfly-reported-distribution-map.

- De Bona, Sebastiano, et al. "LydeMaPR: An R Package to Track the Spread of the Invasive Spotted Lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula, White 1845) (Hemiptera, Fulgoridae) in the United States." bioRxiv, 2023.01.27.525992, doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525992.

- John B. Ward & Co. Arborists, "Spotted Lanternfly", n.d., https://johnbward.com/spotted-lanternfly

- Illinois Department of Agriculture. "Spotted Lanternfly." Illinois Department of Agriculture, n.d., https://agr.illinois.gov/insects/pests/spotted-lanternfly.html.

- Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. "Spotted Lanternfly Quarantine." Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, n.d., https://www.agriculture.pa.gov/Plants_Land_Water/PlantIndustry/Entomology/spotted_lanternfly/quarantine/Pages/default.aspx.

- Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences. "Assessing Economic Impact", https://agsci.psu.edu/research/impacts/themes/biodiversity/detecting-biological-invasions/assessing-economic-impact

- Penn State Extension. "Controlling Tree of Heaven: Why It Matters." Penn State Extension, n.d., https://extension.psu.edu/controlling-tree-of-heaven-why-it-matters#:~:text=Tree%20of%20heaven%20is%20a,across%20most%20of%20southeastern%20PA.

- Penn State Extension. "Tree of Heaven." Penn State Extension, n.d., https://extension.psu.edu/tree-of-heaven.

- Penn State Extension. "What Should You Do with Spotted Lanternfly Egg Masses." Penn State Extension, n.d., https://extension.psu.edu/what-should-you-do-with-spotted-lanternfly-egg-masses.

- University of Illinois Extension. "Spotted Lanternfly Fact Sheet." University of Illinois Extension, https://extension.illinois.edu/sites/default/files/spotted_lanternfly_fact_sheet_v8.pdf.

- University of Illinois Extension. "Tree of Heaven." University of Illinois Extension, n.d., https://extension.illinois.edu/invasives/tree-heaven.

- U.S. Department of Transportaion. "Freight Managment and Operations", n.d., https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/freight_analysis/freight_story/major.htm