Pi-hole includes a caching and forwarding DNS server, now known as FTLDNS. After applying the blocking lists, it forwards requests made by the clients to configured upstream DNS server(s). However, as has been mentioned by several users in the past, this leads to some privacy concerns as it ultimately raises the question: Whom can you trust? Recently, more and more small (and not so small) DNS upstream providers have appeared on the market, advertising free and private DNS service, but how can you know that they keep their promises? Right, you can't.

Furthermore, from the point of an attacker, the DNS servers of larger providers are very worthwhile targets, as they only need to poison one DNS server, but millions of users might be affected. Instead of your bank's actual IP address, you could be sent to a phishing site hosted on some island. This scenario has already happened and it isn't unlikely to happen again...

When you operate your own (tiny) recursive DNS server, then the likeliness of getting affected by such an attack is greatly reduced.

The first distinction we have to be aware of is whether a DNS server is authoritative or not. If I'm the authoritative server for, e.g., pi-hole.net, then I know which IP is the correct answer for a query. Recursive name servers, in contrast, resolve any query they receive by consulting the servers authoritative for this query by traversing the domain.

Example: We want to resolve pi-hole.net. On behalf of the client, the recursive DNS server will traverse the path of the domain across the Internet to deliver the answer to the question.

- Your client asks the Pi-hole

Who is pi-hole.net? - Your Pi-hole will check its cache and reply if the answer is already known.

- Your Pi-hole will check the blocking lists and reply if the domain is blocked.

- Since neither 2. nor 3. is true in our example, the Pi-hole forwards the request to the configured external upstream DNS server(s).

- Upon receiving the answer, your Pi-hole will reply to your client and tell it the answer of its request.

- Lastly, your Pi-hole will save the answer in its cache to be able to respond faster if any of your clients queries the same domain again.

- Your client asks the Pi-hole

Who is pi-hole.net? - Your Pi-hole will check its cache and reply if the answer is already known.

- Your Pi-hole will check the blocking lists and reply if the domain is blocked.

- Since neither 2. nor 3. is true in our example, the Pi-hole delegates the request to the (local) recursive DNS resolver.

- Your recursive server will send a query to the DNS root servers: "Who is handling

.net?" - The root server answers with a referral to the TLD servers for

.net. - Your recursive server will send a query to one of the TLD DNS servers for

.net: "Who is handlingpi-hole.net?" - The TLD server answers with a referral to the authoritative name servers for

pi-hole.net. - Your recursive server will send a query to the authoritative name servers: "What is the IP of

pi-hole.net?" - The authoritative server will answer with the IP address of the domain

pi-hole.net. - Your recursive server will send the reply to your Pi-hole which will, in turn, reply to your client and tell it the answer of its request.

- Lastly, your Pi-hole will save the answer in its cache to be able to respond faster if any of your clients queries the same domain again.

You can easily imagine even longer chains for subdomains as the query process continues until your recursive resolver reaches the authoritative server for the zone that contains the queried domain name. It is obvious that the methods are very different and the own recursion is more involved than "just" asking some upstream server. This has benefits and drawbacks:

- Benefit: Privacy - as you're directly contacting the responsive servers, no server can fully log the exact paths you're going, as e.g. the Google DNS servers will only be asked if you want to visit a Google website, but not if you visit the website of your favourite newspaper, etc.

- Drawback: Traversing the path may be slow, especially for the first time you visit a website - while the bigger DNS providers always have answers for commonly used domains in their cache, you will have to transverse the path if you visit a page for the first time. A first request to a formerly unknown TLD may take up to a second (or even more if you're also using DNSSEC). Subsequent requests to domains under the same TLD usually complete in

< 0.1s. Fortunately, both your Pi-hole as well as your recursive server will be configured for efficient caching to minimize the number of queries that will actually have to be performed.

We will use unbound, a secure open source recursive DNS server primarily developed by NLnet Labs, VeriSign Inc., Nominet, and Kirei.

The first thing you need to do is to install the recursive DNS resolver:

sudo apt install unbound

Optional: Download the list of primary root servers (serving the domain .). Unbound ships its own list, but we can also download the most recent list and update it whenever we think it is a good idea. Note: there is no point in doing it more often then every 6 months.

wget -O root.hints https://www.internic.net/domain/named.root

sudo mv root.hints /var/lib/unbound/

Highlights:

- Listen only for queries from the local Pi-hole installation (on port 5335)

- Listen for both UDP and TCP requests

- Verify DNSSEC signatures, discarding BOGUS domains

- Apply a few security and privacy tricks

/etc/unbound/unbound.conf.d/pi-hole.conf:

server:

verbosity: 0

interface: 127.0.0.1

port: 5335

do-ip4: yes

do-udp: yes

do-tcp: yes

# May be set to yes if you have IPv6 connectivity

do-ip6: no

# You want to leave this to no unless you have *native* IPv6. With 6to4 and

# Terredo tunnels your web browser should favor IPv4 for the same reasons

prefer-ip6: no

# Use this only when you downloaded the list of primary root servers!

# Location of root.hints

root-hints: "/var/lib/unbound/root.hints"

# Trust glue only if it is within the servers authority

harden-glue: yes

# Ignore very large queries.

harden-large-queries: yes

# Require DNSSEC data for trust-anchored zones, if such data is absent, the zone becomes BOGUS

# If you want to disable DNSSEC, set harden-dnssec stripped: no

harden-dnssec-stripped: yes

# Use Capitalization randomization

# This is an experimental resilience method which uses upper and lower case letters in the question hostname to obtain randomness.

# Two names with the same spelling but different case should be treated as identical.

# Attackers hoping to poison a DNS cache must guess the mixed-case encoding of the query.

# This increases the difficulty of such an attack significantly

use-caps-for-id: yes

# Reduce EDNS reassembly buffer size.

# Suggested by the unbound man page to reduce fragmentation reassembly problems

edns-buffer-size: 1472

# Rotates RRSet order in response (the pseudo-random

# number is taken from Ensure privacy of local IP

# ranges the query ID, for speed and thread safety).

# private-address: 192.168.0.0/16

rrset-roundrobin: yes

# Time to live minimum for RRsets and messages in the cache. If the minimum

# kicks in, the data is cached for longer than the domain owner intended,

# and thus less queries are made to look up the data. Zero makes sure the

# data in the cache is as the domain owner intended, higher values,

# especially more than an hour or so, can lead to trouble as the data in

# the cache does not match up with the actual data anymore

cache-min-ttl: 300

cache-max-ttl: 86400

msg-cache-size: 128m

rrset-cache-size: 256m

# Have unbound attempt to serve old responses from cache with a TTL of 0 in

# the response without waiting for the actual resolution to finish. The

# actual resolution answer ends up in the cache later on.

serve-expired: yes

# Harden against algorithm downgrade when multiple algorithms are

# advertised in the DS record.

harden-algo-downgrade: yes

# Ignore very small EDNS buffer sizes from queries.

harden-short-bufsize: yes

# Refuse id.server and hostname.bind queries

hide-identity: yes

# Report this identity rather than the hostname of the server.

identity: "Server"

# Refuse version.server and version.bind queries

hide-version: yes

# Prevent the unbound server from forking into the background as a daemon

do-daemonize: no

# Number of bytes size of the aggressive negative cache.

neg-cache-size: 4M

# Send minimum amount of information to upstream servers to enhance privacy

qname-minimisation: yes

# Deny queries of type ANY with an empty response.

# Works only on version 1.8 and above

# deny-any: yes

# Do no insert authority/additional sections into response messages when

# those sections are not required. This reduces response size

# significantly, and may avoid TCP fallback for some responses. This may

# cause a slight speedup

minimal-responses: yes

# Perform prefetching of close to expired message cache entries

# This only applies to domains that have been frequently queried

# This flag updates the cached domains

prefetch: yes

# Fetch the DNSKEYs earlier in the validation process, when a DS record is

# encountered. This lowers the latency of requests at the expense of little

# more CPU usage.

prefetch-key: yes

# One thread should be sufficient, can be increased on beefy machines. In reality for

# most users running on small networks or on a single machine, it should be unnecessary

# to seek performance enhancement by increasing num-threads above 1.

num-threads: 1

# more cache memory. rrset-cache-size should twice what msg-cache-size is.

msg-cache-size: 50m

rrset-cache-size: 100m

# Faster UDP with multithreading (only on Linux).

so-reuseport: yes

# Ensure kernel buffer is large enough to not lose messages in traffix spikes

so-rcvbuf: 4m

so-sndbuf: 4m

# Set the total number of unwanted replies to keep track of in every thread.

# When it reaches the threshold, a defensive action of clearing the rrset

# and message caches is taken, hopefully flushing away any poison.

# Unbound suggests a value of 10 million.

unwanted-reply-threshold: 10000

# Enable ratelimiting of queries (per second) sent to nameserver for

# performing recursion. More queries are turned away with an error

# (servfail). This stops recursive floods (e.g., random query names), but

# not spoofed reflection floods. Cached responses are not rate limited by

# this setting. Experimental option.

ratelimit: 1000

# Minimize logs

# Do not print one line per query to the log

log-queries: no

# Do not print one line per reply to the log

log-replies: no

# Do not print log lines that say why queries return SERVFAIL to clients

logfile: /dev/null

# Ensure privacy of local IP ranges

private-address: 192.168.0.0/16

private-address: 169.254.0.0/16

private-address: 172.16.0.0/12

private-address: 10.0.0.0/8

private-address: fd00::/8

private-address: fe80::/10

Start your local recursive server and test that it's operational:

sudo service unbound start

dig pi-hole.net @127.0.0.1 -p 5335

The first query may be quite slow, but subsequent queries, also to other domains under the same TLD, should be fairly quick.

Important steps:

In order to experience high speed and low latency DNS resolution, you need to make some changes to your Pi-hole. These configurations are crucial because if you skip these steps you may experience very slow response times:

-

Open the configuration file

/etc/dnsmasq.d/01-pihole.confand make sure that cache size is zero by settingcache-size=0. This step is important because the caching is already handled by the Unbound Please note that the changes made to this file will be overwritten once you update/modify Pi-hole. -

When you're using unbound you're relying on that for DNSSEC validation and caching, and pi-hole doing those same things are just going to waste time validating DNSSEC twice. In order to resolve this issue you need to untick the

Use DNSSECoption in Pi-hole web interface by navigating toSettings > DNS > Advanced DNS settings.

You can test DNSSEC validation using

dig sigfail.verteiltesysteme.net @127.0.0.1 -p 5335

dig sigok.verteiltesysteme.net @127.0.0.1 -p 5335

The first command should give a status report of SERVFAIL and no IP address.

The second should give NOERROR plus an IP address.

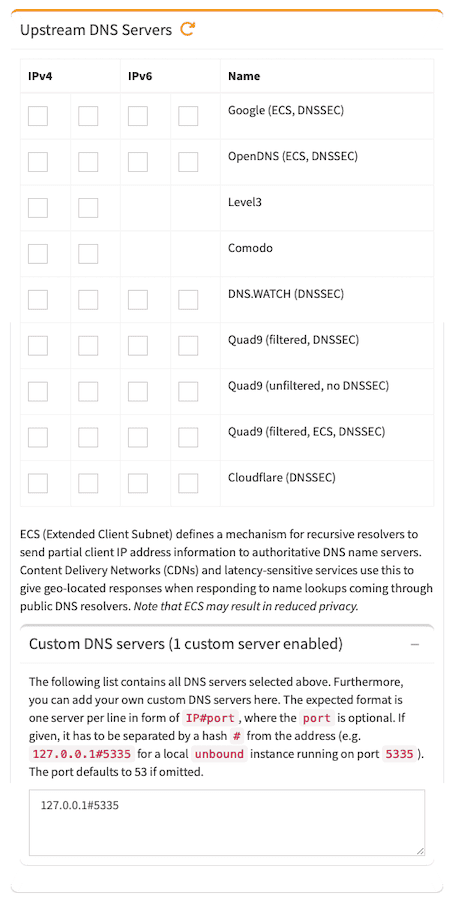

Finally, configure Pi-hole to use your recursive DNS server:

Don't forget to click Save!

All donations are welcome and any amount of money will help me to maintain this project :)