In undergrad, your projects were probably at most a semester long. In grad school, you'll work on projects for years, often with other people. This makes keeping track of what you're doing extremely important.

So how do you do it? Some tips:

- Make it a priority to keep files organized. Don't throw away that stuff from class, you might actually want to go back to it. Spend some time at the end of the quarter and pack everything up somewhere (physically or digitally)

- Record the events you attend and things you participate in (especially things that will make it onto a CV or into a proposal).

- Pay attention to where you're going, both short view and long. There is a thing called an individual development plan. It's actually important, so give it some time and attention.

Finally, record what you're doing day to day and keep things organized. In lab, you keep a lab notebook. For code, we have versioning and git.

This is not just for your benefit! Reproducibility is important for science.

Say you're working on a project and you have a cool result...

To avoid this, you need versioning. Git does that and more.

Git is a version control management system for code. It was invented by Linus Torvalds to support development of the Linux kernel. See this video for more (7:13-9:24). In fact, you can find both Linux and git itself on GitHub. You can even see git's first commit.

For us, keeping track of code with git achieves two objectives:

- Keep a record

- Provide a good way for people to work together on development

In bootcamp wet, you kept a record of what you did in a lab notebook. Why?

- Daily record

- Keep track of goals

- day to day records

- Because I said so

- Standard practice

All those reasons also apply to code. In fact, we should strive to meet an even higher standard for code than we can for lab work, as results don't depend on anything outside of our control (code may have bugs, but it will at least have the same bug every time).

It is possible (and is now easy) to have perfect reproducibility for results of coding projects. This is not yet the standard for scientific publication, but I think it soon will be (and should be the standard we all strive for).

Git makes this easy with the way it keeps a record of the code. In fact it does even better and forces you to document the changes you make. We'll discuss this more later.

Furthermore, along with a host like GitHub, git provides a controlled way for multiple people to work together on a single coding project. Those people can be your lab mates, your PI, or random strangers from the internet.

There are other reasons to use git:

- It is an industry standard. If you get a job working with code, you will likely use git.

- Using git and GitHub to publish code is becoming standard for scientific projects as well. It provides

- Visibility on a recognized platform

- Tools for the greater community to interact with you and your code, as well as for them to contribute to it

- It's a good backup

So git keeps track of different versions of code. How does it do it?

First, we should say:

Git+GitHub is NOT a code specific version of Dropbox

and then, for good measure, we should also say

Git+Github is NOT a code specific version of Dropbox!!!

Dropbox and Google Drive both have rudimentary version control, in that they keep a series of copies of a file. Git is both far more powerful than Dropbox, and more fragile (you will be quite unhappy if you try to add a 7GB database to a git repo). So what is it, exactly?

The basic unit of code in git is a repository (repo). For example, here is a repo by MCSB alum Chris Rackauckas.

Git keeps track of code in commits. A commit is a list of changes. It is not the contents of a file. Here is an example commit from Chris' DifferentialEquations.jl repo. It consists of 9 line deletions and 3 line additions. Along with the list of changes, there is a commit message: a description of what those changes do written by the person who made them.

A repo, then, consists of many sets of changes (commits). You can see the commit history of Chris' DifferentialEquations.jl repo here.

Why are things organized this way, and what does it allow us to do? First, let's talk about branches.

We can think of the commit history of a repo as a series of dots along a line, representing commits made through time. A branch starts at one of these commits and is its own line of dots, running parallel to the first (e.g. master and dev branches below).

Because commits keep track of changes, two branches can be merged back together, even after they have diverged because multiple people are working on them. An example:

Let's say that at a, the code looks like this:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

consectetur adipiscing elit

sed do eiusmod tempor

incididunt ut labore

Ut enim ad minim veniam

quis nostrud exercitation ullamco

laboris nisi ut aliquip

On the dev branch, changes are made so at b the code looks like this:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

consectetur adipiscing elit

sed do eiusmod tempor

incididunt ut labore

et dolore magna aliqua.

Ut enim ad minim veniam quis nostrud exercitation ullamco

laboris nisi ut aliquip

ex ea commodo consequat.

Meanwhile, changes have been committed to the master branch so that at c, the code looks like this:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

consectetur adipiscing elit

sed do eiusmod tempor

incididunt ut labore

et dolore magna aliqua

Ut enim ad minim veniam

laboris nisi ut aliquip

Duis aute irure dolor

in reprehenderit in voluptate velit

esse cillum dolore

eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

A merge is then initiated, where changes from the commits to the dev branch are applied to the code as it exists at c. At d, the merged code would be:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

consectetur adipiscing elit

sed do eiusmod tempor

incididunt ut labore

et dolore magna aliqua.

Ut enim ad minim veniam quis nostrud exercitation ullamco

laboris nisi ut aliquip

ex ea commodo consequat.

Duis aute irure dolor

in reprehenderit in voluptate velit

esse cillum dolore

eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Note that both sets of changes are kept.

What happens if both branches had changed the same line? Then the merge needs human intervention --- git would prompt you to choose what to keep.

Note that there can be many branches, all working in parallel. They can be merged with each other at any time.

- Linus' dream is fulfilled --- he doesn't have to talk to another human to incorporate their code into his repo. The commit message tells him what the person what tyring to accomplish and what specific changes in the code they made to do so.

- This applies for you too --- you in three years definitely won't remember what you right now was trying to accomplish

- Each commit is identified by a unique hash. This means if we know the commit hash that was used to generate some result, we know exactly what the code was. No questions of "did I change that before or after doing that plot?"

- This means that things can be perfectly reproducable

- The independent work of multiple people (working at the same time) can be combined in an easy way. No confusion about what version of the file peope are working on

- This is especially useful for writing papers, where a great deal of confusion can happen with file versions being emailed back and forth. Latex in particular is just code like any other language and goes very nicely with git.

Now that we know what git is and what it does, how do we use it to manage code for a project? First, let's do an overview of what is where.

def: "a set of principles laid down by an authority as incontrovertibly true"

- Data does not go in a git repository

- Note Github has hard filesize limits and git itself will be slow and unhappy with files larger than 10MB or so

- Commits should be atomistic --- they should accomplish one objective (e.g. Take in radius as an input variable). This might involve changes to more than one file.

- Commit messages should be written in the imperative mood (e.g. fix, update, not fixed or updated)

- More on this and examples can be found in this write up

- Think of "This commit will _______"

A repo can live on your computer, on a remote host (we'll use GitHub, but there are others), or preferably both. If both, changes can be synced back and forth from your computer to the web, and to other computers easily and in a controlled way.

Here's a map of how one coder can use GitHub to sync code between computers:

From your computer, you can git pull to get commits from GitHub. You can git push to send commits you've made to GitHub. Therefore you can work on the same repository using multiple computers (say a laptop and a desktop in your lab).

Here's a map of how multiple coders can use GitHub to work on code together:

For a second coder to join the first, they first fork the repo on GitHub. This forked repo is their own version, which they have total control over. They can work with is as described in the previous section. If the make changes they want to share with coder 1, they go back to GitHub and submit a pull request: a request for coder 1 to pull commits they've pushed up to their repo.

As I'm sure you've noticed, this is a git repository hosted on GitHub. We're going to get started using git with this repo!

We're going to use the command line. Here's a quick primer:

pwd: prints the current working directoryls: get a list of all the files and folders in the current directorycd target: change to the directory specified by targetmkdir: makes a folderrm: deletes- typing the first few letters of a file or folder name and hitting tab will complete the rest for you

- the up arrow will take you back through the history of your commands, allowing you to reenter them

Some examples follow. Let's take a folder on my computer as an example. Here's the output of pwd and ls:

birch:project_code Matt$ pwd

/Users/Matt/project_code

birch:project_code Matt$ ls

ActinTutorial bootcamp-test

Motor-Cargo-Simulator test folder

Note pwd prints the full path, which starts with a "/" indicating the root of the filesystem. Then, from this location, we could do any of

-

cd ActinTutorial: moves into folder ActinTutorial -

cd ..: moves up a folder to /Users/Matt -

cd ~: moves to the home directory, for me /Users/Matt -

cd test\ folderorcd "test folder": moves to test folder. Note spaces need to be escaped or quotes be used. If you don't, you get:birch:project_code Matt$ cd test folder -bash: cd: test: No such file or directorybecause spaces separate inputs on the command line

Say we did cd .., moving to /Users/Matt. We could then move several folders at once with cd project_code/Motor-Cargo-Simulator/simulation_code, which would take us to the simulation_code folder inside the Motor-Cargo-Simulator folder.

If we then wanted to return to /Users/Matt, we could use cd .. three times, cd ../../.., or cd -, which returns to the last directory.

Now our goal is going to be to get this repo to your computer. First, we need a place to put it.

Let's make a place to put all the files we'll be working with in bootcamp. First, note that you SHOULD NOT put a git repo in an auto-syncing directory (Dropbox, Google Drive, iCloud, OneDrive). For windows users, make a folder

/mnt/c/bootcamp_dry

Mac users, make folder

/users/username/bootcamp_dry

also can be found at ~/bootcamp_dry

Go to your file browser (explorer or finder) and find the folder you just made.

Go to the root page and use the grey "Fork" button at the top right to get your own version of this repository. On your version, use the green "Clone or download" button to copy the address of your repo.

Now, back in the command line on your computer, navigate to the folder you made. Confirm that pwd retuns either /mnt/c/bootcamp_dry or users/username/bootcamp_dry.

Type "git clone ", then paste the link (right click on Windows Ubuntu, ⌘+v on MacOS). The command should look like

git clone https://github.com/yourGitHubusernamehere/MCSBBootcampDry.git

(but with your github username). This command will download the repository from github.com to your computer, putting it into the present working directory.

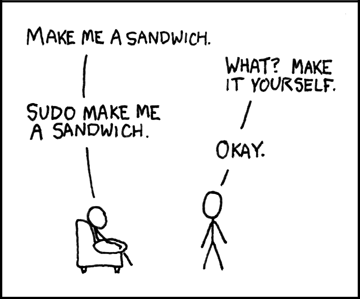

If you get a permissions error, try sudo git clone https://github.com/yourGitHubusernamehere/MCSBBootcampDry.git. This executes the command with elevated permissions and is generally the answer when something doesn't work.

Now that we have the repo on your local computer, we want to get your repository set up so that you can use it smoothly.

You'll have two branches:

- "master" branch: Keep this branch clean of your personal work. However, if you have suggestions for changes you think everyone should have (typo fixes, additional links, other improvements) feel free to commit them here, push them up and pull request allardjun/MCSBBootcampDry

- "exercises" branch: Add your personal work to this branch

To set up your repository this way, first go into your new folder

cd MCSBBootcampDry

Then you can check that everything is working with git status. It should return

birch:MCSBBootcampDry Matt$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

This tells you that you are on the master branch and haven't made any changes yet. Now we'll create a new branch called "exercises".

git checkout -b exercises

Then status should return

birch:MCSBBootcampDry Matt$ git status

On branch exercises

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Now that you have a place for your work, let's add something to it.

First, make a new folder

mkdir mywork

ls should reveal it is there. Navigate into it with cd and make a new text file

vi mytextfile.txt

This will bring you into the vi command line text editor. This is a dangerous place for beginners, as there are no instructions for how to get out! (esc doesn't work, if you were thinking that would save you)

When you open the file, you are in command mode. There are many possible commands that navigate the document, delete lines, etc. However, since our document is blank, we want to go into insert mode. To do so press i. The bottom of the screen should say -- INSERT --.

In insert mode, you can type, backspace and delete as you probably expect. Type your name.

Now, we want to save the file and exit. To do so, we need to go back to command mode. Press esc. -- INSERT -- should disappear from the bottom of the window. Now type :wq. You should see it appear at the bottom of the window. This mean write-quit. Press enter. You should be returned to your command line and ls should reveal a new text file in your directory.

At another time you might want to quit without saving. To do so you would use :q.

Now that you have the ability to create, you should also gain the ability to destroy.

- Create a new directory called baddir

- Navigate into it and create a new file called badfile.txt, with any text you'd like to add to it.

The command to delete things is rm. Delete both the file and folder you made.

Now that we've created something we want to keep, let's commit it.

Go to the root of your repo (cd .. if you're in the mywork folder)

git status should reveal that you have changes to your repo.

The commit process has two steps: staging and committing.

The command to stage is git add target. Target can be a file, folder, or ., which means everything.

Stage with git add .

git status should give you

dhcp-v021-085:MCSBBootcampDry matthewbovyn$ git status

On branch dev

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: mywork/mytextfile.txt

Commit with git commit

At this stage, you may be asked for credentials. Enter them now.

Recognize this interface? Just like vi! Enter a good commit message (imperative mood!) and save with :wq.

Note that commit messages are extremely important. They are not easy to change, so think about what you are writing. Furthermore, other people will see them. Keep that in mind.

Time saving tricks for future use:

git commit -adoes an automaticgit add .(or something like it, doesn't seem to add new files)git commit -m "Commit message here"lets you skip the text editor if you want a one line commit message- Can be combined into

git commit -a -m "Commit message"

To send your commit up to GitHub, git push. Try it now.

git push is the short form. The long form is

git push origin exercises

where origin is the name of a remote address (e.g. https://github.com/yourGitHubusernamehere/MCSBBootcampDry.git). exercises is the name of the branch you are pushing.

You will definitely be asked for credentials at this point (unless you already have them saved).

Before, we made updates to this markdown file based on the reasons you stated for having a lab manual. As practice, let's get those changes from Matt's computer to all of yours.

Matt does:

- Examine and commit changes

- Push to mbovyn/MCSBBootcampDry

- Pull request allardjun/MCSBBootcampDry

- Approve pull request

Students do (starting from exercises branch):

Add a remote for the allardjun/MCSBBootcampDry repo

git remote add upstream_allardjun https://github.com/allardjun/MCSBBootcampDry.git

Pull down changes and merge them into the dev branch

git status(if working tree is not clean, git won't let you do anything until you commit or discard any changes you've made)git checkout mastergit pull upstream_allardjun mastergit checkout devgit merge master

These steps can be repeated in the future to pull down other changes from allardjun/MCSBBootcampDry. If you wanted to pull down changes from e.g. mbovyn/MCSBBootcampDry, you could add the address of that repo as a remote, or just

git pull https://github.com/mbovyn/MCSBBootcampDry.git master

using the address directly without saving it as a remote.

A bit more dogma:

- All plots must have descriptive axes labels with units

- A figure without a caption is like Ikea furniture without an instruction manual: might be worthwhile if you already know exactly what you're doing, but more likely will just lead to frustration, defeat, and possibly everlasting hatred.

In this section, we'll explore what happens if you don't follow these rules.

First, we'll assign numbers to everyone (4-21). After that follow these instructions on your own.

git status should return something like

Matthews-MacBook-Pro:MCSBBootcampDry matthewbovyn$ git status

On branch exercises

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/exercises'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Open Atom. File -> add project folder -> select MCSBBootcampDry

Go into the figure_legend_exercise folder and open Figure2.md. Open the markdown preview of this code using ctrl+shift+m.

This is code in Markdown, a typesetting language. Look at Markdown in 30 seconds.md to learn a bit about it.

Replace any instances of ??? in the line corresponding to your number with whatever you see fit.

Once you've made your change, look for the Git button at the lower right hand corner of the Atom window. Use this interface to commit your changes.

There is also a button to push. Use that to push your changes up to Github.

Go to your repo on Github and use the green pull request button to pull request your changes to the vstudent branch of allardjun/MCSBBootcampDry

Once all the pull requests are in, I'll approve them and we can read the figure we've created.

Hopefully this exercise has demonstrated both that your should clearly label your graphs (with descriptive labels, not just letters).

It was also meant to demonstrate that all of us could make changes to the same thing, then we could put all those changes together to complete something. It simulated the task of paper writing with collaborators, but hopefully you can tell that it is equally applicable to code.

Someone else's lesson on how to use git: http://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/

git documentation: https://git-scm.com/docs