Today, we're going to build a program that uses a Command Line Interface (CLI). That means that the user will interact with it from the command line, just like you do. Here's what it might look like:

The demo shown above is pretty cool at first, but it's also fairly basic. Don't let that fool you - the CLI project can evolve into some of the most interesting code you've written thus far.

Before we jump in, we need to have a pretty good idea about what the command line calculator could eventually become. There are so many different types of calculators out there:

- Calculators that convert feet to meters

- Calculators that tell you your BMI based on your height and weight

- Calculators that compute the cost of a Lyft or Via ride

Before you code out your calculator, take some time to let your imagination get ahold of this project. What types of calculators are there? What would be helpful to you in your everyday life?

The highest level version of what this calculator can do is pretty impressive, but an important part of this process is designing what we call an MVP - a minimum viable product.

A Minimum Viable Product has only the core features necessary to make it useful to a user.

You see evidence of this design mindset almost every time you start up your phone - most of the apps you have get updated a few times every couple of months - that's because great programs are never TRULY finished, so no company can afford to wait until an app is perfect to release it. Instead, great design teams think in terms of features. They make a short-term, manageable goal that will get them one step closer to their larger goal.

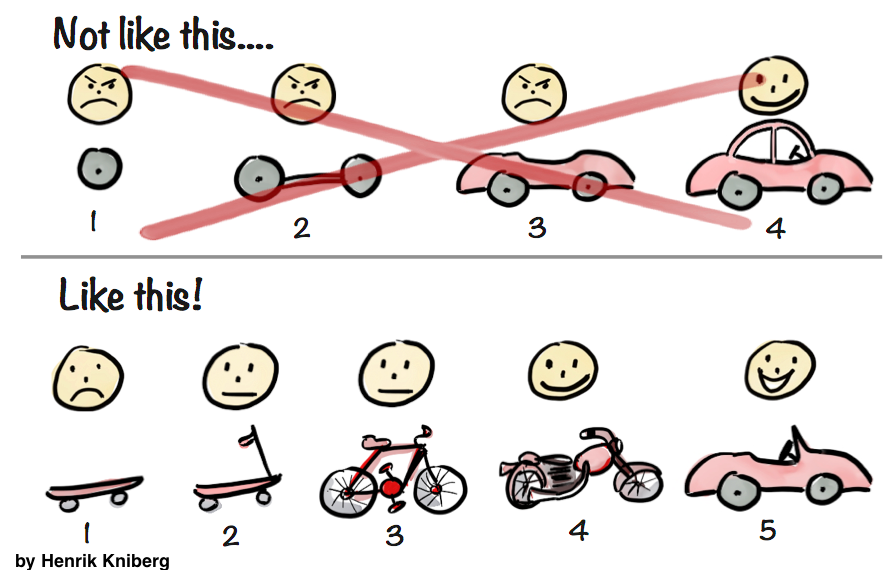

Here's a great cartoon that illustrates this design process:

Art credit: Henrik Kniberg

The cartoon uses the analogy of building a car, and as designers, we are tempted to try to build the perfect wheel before we move on to the next step of a car. The trouble with that design strategy is that you won't be able to test anything or use any part of the program until the whole thing is finished. This is a frustrating process because you spend most of your time building something that you're not even sure if you can build.

Instead, the second design strategy involves building the simplest version of something that works in the same way the car ultimately will. Sure, it's not a full fledged car, but you can start testing it and learning how to make it better so much sooner - it may not be perfect, but it already works! From here your users can test it out and give you feedback on how to make it better. This design process is so satisfying because it works right away; you'll experience success over and over again when you use this strategy.

Because this is the first time that many of you have implemented the MVP design process, we're going to recommend what your first few versions should be:

Additional features of your choosing (love calculator? name rater? pythagorean theorem? quadratic solver?)

You're welcome to organize these differently, but this is a really good place to start.

If you feel like you've added everything you and your team originally set out to do, that's completely fine. Here are some probing questions you can ask your team to see what a good next step might be.

- Does your calculator handle negative numbers correctly?

- Can your calculator handle decimals?

- Can your calculator tell whether the user enters something silly like "five plus seven" instead of "5 + 7"?

- Does your calculator need to be restarted after every calculation? Is that what you want?

- What repetitive things do you often have to do in math class that you wish were easier? Can you make this calculator do those things?

- What happens if your user enters invalid data into your calculator?