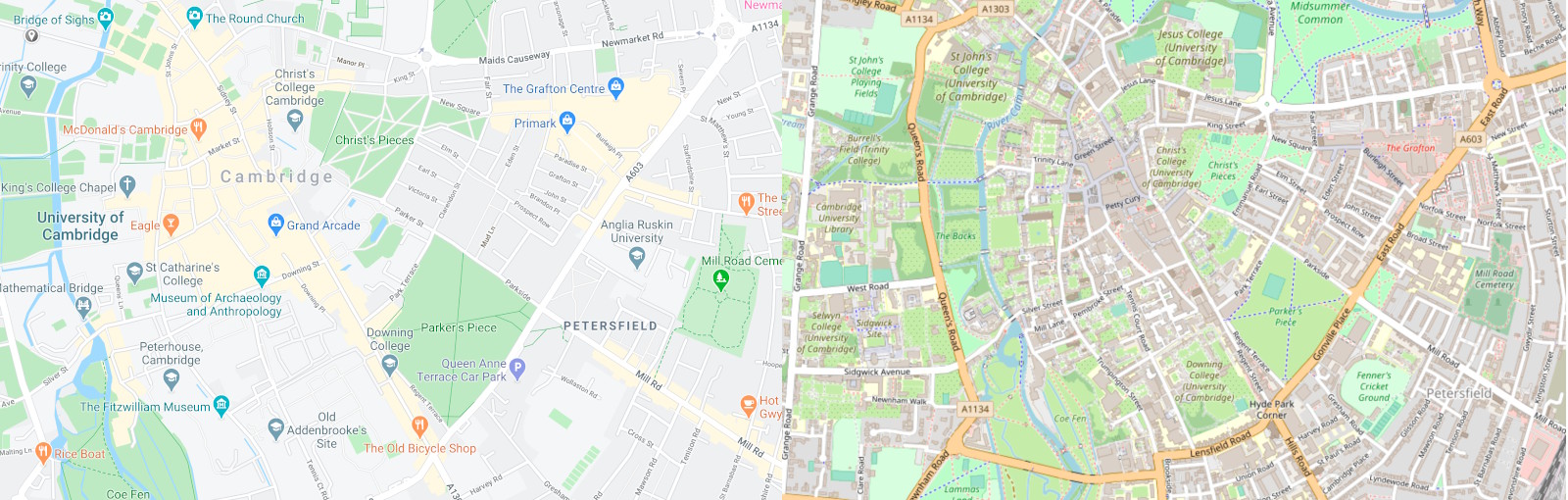

Working on this field (trying to research for a PhD in the anthropology of civic tech) has been eye opening. There is no agreement on what any of these names seem to mean. I often end up playing a game with my participants called "Civic or Not?" putting different products next to each other and asking whether they feel civic. For example: google maps and open street map. One emaphasises businesses I should visit and one emphasises cartography. They have different underlying philosophies. They are visibly similar, but built on different philosophies.

I'm reminded of Tom Loosemore's post on "govtech" here. There is more than one type of civic tech. The scottish government's CivTech accelerator (that for some bizarre reason they've trademarked) which is almost definitely govtech by any other definition, or how people in the US seem to describe the work that GDS et al do as civic tech.

The reason I bring it up was a hack day over the weekend that was explicitly for right-leaning/conservative techies. And it got me thinking about some of these definitions again. A few people's responses to the event suggested that it was very much in keeping with the spirit of hack days of the 2010-2015 flavour - people working on projects that help new MPs get set up, help government communicate better with people. But something that had struck me six years ago when I used to attend a lot of these sorts of hack days (which the memory hole has absolutely chewed up) was that there was often a playful sense of opposition. Hacks like using food standards data to find the dirtiest (read: best) kebab place near you, or merging the photographs of MPs together to prove that in aggregate they look a bit like Richard Madeley.

There are a lot of routes you can go down that aren't helpful here. To start with, there is probably something about what is involved in making the world better if you think that the ideas in a particular party manifesto are "civic". So, let's leave the disection of any party's ideas to one side, because I think there is another more useful point here.

I would suggest that civic technology sits orthogonally to political power. It is /satirical/ and resistant. It is not an insurgency, but it lets you see the loopholes in the status quo. It's a response to power, not a handmaid to it.

Civic tech projects around the world are often about resisting the rise of an authoritarian state (as in the case of NOSSAS in Brazil), or more prosaically, about giving citizens the tools to hold power to account. What they don't tend to be are tools to help those in power act more efficiently. Universal Credit doesn't have a civic tech scene helping DWP get more data on benefits claimants, it has people like Citizens Advice helping people survive and navigate a remote and unfeeling system.

I'm not saying this shouldn't exist. It's fine, and frankly, the projects being done seem good hearted. And other explicitly party political groups exist and do really interesting politically driven tech work. But I wonder what people think the relationship between power and technology is here. A lot of the networks that sprung up in the first wave of UK civic tech seemed to have a lot to do with NO2ID and other civil liberties groups, and also out of a particular post-Iraq invasion point that was disillusioning for many. I think the times have changed radically and the context of both politics and the internet are incomparable to 2010. But, having technologists from a wide(-ish) range of backgrounds can help prevent silos or bubble thinking. It might not matter if you're making a hack to turn emails into faxes but when those projects become infrastucture, the politics and the philosophy of them will matter more.

The interventions of 10 years ago don't seem as relevant to the problems in front of us now. And we have been burned enough times by not analysing the power structures behind technology.