| title | description | version | authors |

|---|---|---|---|

Design is the bottleneck to building new features |

Reduce Volatility is the Marginal Cost of *Implementing* New Features |

v0.1.0 |

see sources and references |

Web3 Design Postulate

✅ The cost to build new features is the bottleneck: Design

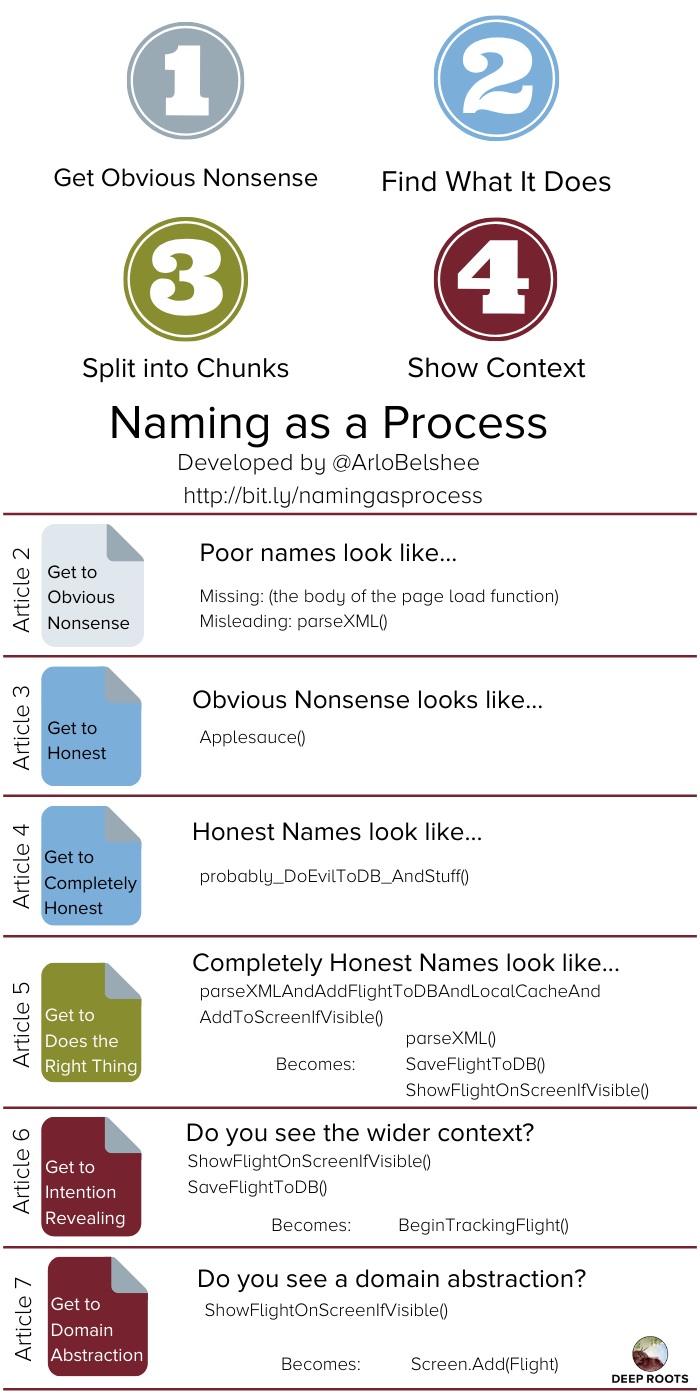

- Deep Roots - Naming as a Process (Article 1)

- Deep Roots - Get to Obvious Nonsense (Article 2)

- Deep Roots - Get to Completely Honest (Article 4)

- Deep Roots - Get to Intent Revealing (Article 6)

- References

These are some axioms of modular design.

Whether you end up with procedural, object-oriented, or functional design depends mostly (only?) on how you choose to organize your functions.

Simple design is about organizing code so that we can find the thing that we need to change and we use tests so that we can change it safely and that leads to four elements of simple design these are:

- Passes its tests

- Minimizes duplication

- Maximizes clarity

- Has fewer elements

The Two Elements of Simple Design

source: https://blog.jbrains.ca/permalink/the-four-elements-of-simple-design

There are two key elements of simple design: remove duplication and improve names. When you remove duplication, you tend to see an appropriate structure emerge, and when you improve names, you tend to see responsibilities slide into appropriate parts of the design.

Therefore, we can call a design simple to the extent that it:

Passes its tests- Minimizes duplication

- Maximizes clarity

Has fewer elements

source: https://www.digdeeproots.com/articles/naming-as-a-process/

Many people try to come up with a great name all at once. This is hard and rarely works well. Here is an iterative approach.

We all know naming is a pain in the ass and you can’t trust the names in your code. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Many people try to come up with a great name all at once. This is hard and rarely works well. The problem is that naming is design. Here are the things you are typically trying to do all at once while naming:

- Deciding the things the code should do

- Deciding which things go together

- Deciding which abstractions best represent those clusters

- Picking a name that clarifies intent

- Picking a name that distinguishes from all the other similar intents

- Describing the side effects of the code

- Keeping your name under 15 characters

This is why naming is hard.

Our brains can’t juggle seven cognitively complicated tasks at once. After brain overload, most of us give up and settle for a crappy name.

Naming something perfectly the first time isn’t going to happen. Let’s talk about evolutionary naming.

The easiest approach for finding good names is to progress along a series of regular steps.

At each step, I look at one part of the code, understand one kind of thing that is happening, have an insight, and write it down. I repeat this until I have moved one step down this list. I keep going until I have a good enough name for my purpose.

Those of you who are reading ahead will wonder why I am focusing on names. I mean, names are annoying to come up with and perhaps this will make it easier, but is that really a problem?

The answer to that question lies at the heart of understanding, preventing, and paying off technical waste.

Wasteful code is any code that is hard to scan. Technical waste is anything that increases the difficulty of reading code.

Me.

My focus on code reading may seem odd to many of you. After all, we’re programmers. We’re good at reading complex code, and our job is to update code. Shouldn’t the definition of technical waste be something about the cost and risk of changing code?

This is.

It turns out that the largest single thing developers spend time doing is reading code.

More than design. More than writing code. More than scanning. And yes. Even more than meetings (well, probably).

According to an analysis from Eclipse data, programmers spend around 60-70% of their entire programming time reading code.

So if we want to be more efficient, we need to improve our ability to read code.

Bugs aren’t random. Unsurprisingly, bugs get written more often when:

- methods are long or deeply nested (cyclomatic complexity),

- concepts are spread around,

- code does multiple things,

- there are side effects.

Make a method longer or make code more complex to reason about and people write more bugs when they edit it.

But those aren’t the #1 cause of bugs. Poor naming was #2 but became #1 when inconsistent indentation was solved by IDE’s.

Now that we know bugs aren’t random, let’s look at what leads to a bug.

- Mistakes happen when our mental model doesn’t match the reality of the code.

- Neuroscience shows that our short-term memory only has seven registers.

So if the real code would take more than seven registers to model, we can’t help but write bugs. So let’s make the code take fewer registers. Since it takes more registers to comprehend code than to remember what it does, the easiest way to reduce registers is to make the code easy to comprehend.

So if our definition of technical debt is code that is difficult, expensive, or risky to change, then the root cause of that is code that is hard to scan. And what makes code easy to scan? Good names.

Definitions are where we communicate instructions to the computer. Names are the place we communicate our insights and intentions to other humans.

Remember, the annoyingly simplified solution is to have one insight at a time, write it into a name, and repeat until your name shifts to the next stage. The remaining challenge is to learn how to make each kind of naming shift. For each stage you will need to know:

- where to look for insights,

- what kinds of insights to glean,

- how to write them down in a name,

- how to use tools to do this at speed, and

- how to know when you are done.

The two most terrible kinds of names are also the most common:

- Names that mislead you, and

- Important parts of something else, so they don’t even have a name.

In the spirit of naming as a process, we want a quick way to fix these two problems. It needs to be trivially fast and light, so that we can do it the hundreds of thousands of times that most codebases need.

We will turn Missing and Misleading into Obvious Nonsense.

Obvious Nonsense isn’t great, but at least it isn’t misleading! Now it becomes obvious to everybody on the team that the name is nonsense and they won’t be tricked into writing a bug.

Why start there? Making code readable is our ultimate goal, however often code has many different concepts in the same method/class/field/variable. We want to pull out each concept and give it a name. When a concept is embedded within another thing, we can see its name as missing.

Focus on long things that are related to the task at hand; the long methods, long classes, long files, long argument lists, long expressions. All of these are more readable and consumable when broken into pieces with one concept each.

I look around for things that seem to go together. Examples include:

- A paragraph of statements

- A non-obvious expression (usually involving arithmetic or logic)

- A set of parameters that are frequently passed together.

- A set of parameters that are used together in the method (such as a bool which indicates whether another variable is valid)

I just pick one chunk that hangs together. It doesn’t really matter how good a chunk I find. There are techniques that will find better chunks and speed up my understanding, but any chunk will get me one step closer. We can leave refinement for later. Good is too expensive; all I want is better (quickly).

We want to understand this lump of stuff. The first step is to create a thing to be named. Typical languages allow us to name any of 5 different things, so we must create one of these things. To do this, we use one of 5 refactorings:

- Extract Method (to name a bunch of statements)

- Introduce Variable, Parameter, or Field (to name an expression)

- Introduce Parameter Object (to name a set of parameters that are passed around together)

We want an Obvious Nonsense name, so use Applesauce. Everyone on the team will instantly recognize it as nonsense. Also, because there is only one nonsense name, you will need to make this name honest (the next step) before you make more nonsense in the same scope.

Obvious nonsense feels unprofessional. It’s not how you want to represent your work. Creating bugs, however, is more unprofessional – we are just more used to it and have come to accept it. Things that contain many unnamed concepts are difficult to reason about, which will cause developers to write bugs.

The self-directed and coached habit changes for this process address common resistances, including the urge to take the time to create a good name.

There are a few ways for you to hone your chunk-finding skills. Once you’re in a long method and you see that there are possible missing names, use these strategies to find the best pieces to break out.

Long methods tend to be organized as:

- Guard clauses

- use parameters to read the data the method wants into local variables

- process

- calculate a result

- either write it down somewhere or return it.

This means that the more important stuff is near the end of the method. So start looking for chunks from the bottom, not the top.

This also makes extraction easier in most languages, because functions often allow multiple parameters but only one return value. So it is easier to flow messy information (like a bunch of local variables) into a function than out. This is not a problem in languages with functions that have the same cardinality for both parameter lists and returns (support destructuring return like Python or support only one parameter like Haskell).

In general, you’re not reading code for the joy of reading it. You’re trying to accomplish something. Use that something to guide what code you bother reading.

Use binary search to quickly find highly relevant chunks. Look for large chunks that don’t contain whatever it is you are seeking or small chunks that do. Either quickly reduces the search space.

Foreshadowing a bit into the next step, when you extract a large chunk of code you know to not be related, just get the name up to barely Honest and then move on. For example, you could call it probably_DoStuffUnrelatedTo[whatever]()].

Long methods are often dominated by a single control structure (after the guard clauses and fetching data into locals). The body of that control structure is often a good target. If there are multiple control structures in sequence, instead take the whole last control structure.

For example, if a method BecomeFroglike() contains one giant foreach loop, extract the body of the loop and call it MakeOne[whatever the control variable is]BecomeFroglike().

And if a method contains a foreach loop, then an if block, then another foreach loop, extract those into three methods, each taking the whole control structure. The outer method is then just a series of 3 method calls in sequence.

Exception handling is a little special. The body of a try block is often a good target for extraction. I usually name the resulting function *_Impl(). Complicated catch blocks are usually not worth extracting (though there are exceptions), so instead, look for ways to extract the useful bits away from them.

Another common challenge to reading code is when the name is indicates something different than what it does. When a concept is not being represented accurately by the name, we say its name is misleading.

Focus on whatever names you encounter in the code you are reading.

I look around for partial lies. Examples include:

- A method is named by when it is called in a lifecycle (PageLoad, PreInit).

- A variable named the same as its type (GridSquare gridsquare).

- Method name that leaves out critical information (method named composeName that also writes that name to the database).

- Any name that ends in -er or -Utils (DocumentManager, CalculationUtils).

Don’t bother trying to figure out what it does or a good name for it. Just call it Applesauce and move on with your coding. We have the social norm that should always be good; however, if the name is misleading, even if it looks good, is not good. Misleading names will cause someone to write bugs.

I used to consider whether to check in at this point. It feels so small, and Applesauce feels like such a terrible name!

After 4 more years of practicing this, however, I no longer consider. I always check in.

Both of these changes make the code better. Not a lot better, but better. They are fast, easy, safe, and don’t make anything worse. By checking them in I immediately get back to a clean slate and am ready for whatever comes next.

Replacing a missing name tends to result in more insights about the code, so it is likely that both this commit and the next will be large. I want to split this up from that. Replacing a misleading name will almost always prevent one future bug. It is worth checking that in immediately so that there is no chance a failure at my next task will roll this back. Either way, check in now.

I need to make my name fully describe everything this method does. Each level of improved naming should record more insights and make it easier for the next person to read the code.

This level actually makes it unnecessary for the next person to read the code. We want them to be able to trust that the name includes absolutely everything the method does so they can read and understand calling methods without having to read the method we’re fixing.

In the previous articles of this blog series, everything being done was accomplished in one step. However, being completely honest is hard so we need to take it in steps.

Each time you iterate on an honest name by making it more honest, you’ve made it easier on the next coder. A name might progress through this phase over the course of weeks or months. Eventually, though, the name will have become completely honest.

To complete “one more iteration” of the name becoming more honest, we look through the body of the method and find one of two things:

- Expand the Known: find one more thing that it does. Add it to the name.

- Narrow the Unknown: find one specific thing that we don’t know. Add it to the _AndStuff part of the name.

The first option in your iteration of making the name more honest is simply finding one more thing that it does, which is explained in these three parts.

You know this by now. It is often useful to look for paragraphs or control structures.

The process is:

- Find one thing that the code does (an effect, a calculation, a result, a state change).

- See if that is already included in the name (it might be a legitimate substep of something that is already in there).

- If not, add it (see Part 3).

Don’t broaden the parts of the name. Your goal is not to find one abstraction that includes everything the method does. Your goal is to be precise; a reader should be able to read the method name and know exactly what the method does.

Ignore everything you’ve been taught about naming conventions. Long names are good. Conjunctions are good. Belaboring the point is good. Your only goal is to make sure that everything this thing does is represented in the name. And therefore anyone can trust the name. They no longer have to read the thing, just its name.

Imagine emailing the method name to someone. Just the name. Would they be able to generate exactly all of the things in the method body? They shouldn’t want to add any more things and they shouldn’t miss any.

The purpose of the second section (middle) of the name is to simply record what is known. Recall from previous articles that probably_ flags the team that there is uncertainty. _AndStuff records what is not known, while the center lists everything that is known. So add your new clause to the middle section.

The second option in your iteration of making the name more honest is finding one specific thing that we don’t know, which is explained in these three parts.

If you’re looking inside the body, focus on data or parameters you haven’t analyzed yet. This will help you add a clause to the set of unknowns.

Another strategy to consider is to:

- Look at the name of the method,

- Pick one of the clauses of unknowns that you want to narrow, and

- Look at the parts of the method body that are related to that clause.

As the title suggests, you are looking for a category of things that the code doesn’t do, but also look for one partial truth for something the code does do. Let’s look at some examples.

Something that it doesn’t do Assume that I have a name AndDoSomethingWithGraphicsContextAndStuff(). I realize that the method doesn’t write to the GC or use it to draw anything; it is read-only. I might name it to AndDoSomethingReadOnlyToGraphicsContextAndStuff(). I don’t know what it does, but I’ve reduced the unknown.

A partial truth about what it does do

Assume my name includes AndDoSomethingToDatabaseAndStuff(). I discover the code opens a write cursor and no reads, and rename to AndWriteSomethingToDatabaseAndStuff(). I don’t yet know what is written, but I’ve exposed a partial truth and reduced the unknown.

The process is:

- Identify one piece of data related to what you’re looking for (that may be a variable, parameter, or field).

- Trace that data’s usage through the method to find one thing that is either done or not done with it.

- Update the name accordingly (see Part 3).

The purpose of the _AndStuff section of the name is to record and quantify the unknown behaviors of this method. That is why we start simply with _AndStuff. However, now that you are moving from an Honest Name to Completely Honest, we can provide more precision than _AndStuff. So now you are going to record the more precise information you have by adding a clause to _AndStuff.

A Completely Honest name will include only the middle section.

To get rid of the third section, we have to eliminate the last unknowns. We will need the object to be so readable that we know for a fact it doesn’t do anything beyond what we’ve said. It is usually easiest to identify all the impacted data and generate specific clauses in the third section. Once we’ve traced all the data, we know there can be no other impacts, so we can remove the general AndStuff(). Then we simply have to chase down every unknown clause one at a time until the third section is gone.

To get rid of the first section we have to be confident in the rest of the name. The probably_ indicates that we are not yet sure. To become confident we will need two things. First, we will need tests that verify the method does everything we say it does in the middle section. Second, we will need the object to be so readable that we know for a fact all unknowns are scoped by the third section. Once both are true, we can eliminate the probably*. However, later editors than need to either be justifiably confident in their naming steps or re-add the probably*. For this reason, removing the probably_ is often the last step.

Sometimes understanding a subcomponent requires extracting it and getting it to have a better name. This is especially common with long methods. When you do this, keep your focus on the main name. Extract a chunk and record insights only until you know whether it is important for naming your main thing. Then update the main name and move on.

Guard clauses are a good example. They’re usually easy to identify but take up a bunch of space. I won’t use them in the name of the thing (most of the time), but they can make it hard to read the rest.

I’ll extract a bunch of what I think are guard clauses, get the name for the extracted component to be Honest, and see if they are all guard clauses. If so then I leave them alone and come back to the main method.

I’ll extract guard clauses until I’m left with the residual. Then I’ll analyze that more deeply and make sure I get everything into the name of my main method. I might inline the guard clauses again when I am done, or just leave them named something like ValidateAllInputs().

In the example from the FAA issue I shared in Article 3, I needed to take several steps to find all the things my method was doing. I eventually identified 4 main chunks of functionality, each of which happened in many steps. So my method became parseXmlAndStoreFlightToDatabaseAndLocalCacheAndAddToScreenIfVisible().

This step also applies to variable and class names.

- Classes should be named by all of their responsibilities.

- Variable names should include all the ways the variable is used. In deep legacy, code variables may be used in a surprising number of ways. An example is once when I had a poor, overused in/out parameter that I had to name searchHintThenBestMatchSoFarUntilItBecomesReturnValueOrReasonNoMatchWasFound.

There is a strong design rule that says classes should have a single responsibility. That’s true. However, in this step we are ignoring what “should” be true and trying to simply be completely honest about what is true right now. Classes often have a primary responsibility while also including a couple of other responsibilities that mostly make sense and are too small to break out. That being said, this naming stage is simply being completely honest about all of those responsibilities. We will decide what to do about the multiple responsibilities in the next step.

Here the insights that I’m having are all the important characteristics of the thing I am naming. I’m naming it by what it does, not by what it is. This shift is a critical step in eliminating god classes and long methods.

- *Named by what it is…**When a thing is named by what it is, then it accumulates everything vaguely related to that identity. Use this when you want other coders to naturally gather related pieces of functionality from other code and increase cohesion.

- *Named by what it does…**When it is named by every single thing it does, then our desire for shorter names drives us to have it do less stuff. Use this when you want other coders to break it apart and simplify each chunk.

How something is named will drive the behavior of how people will engage with it and the future evolution of the method, variable, or class.

Every improvement in our name until now has focused on what our class/method/variable does. We made it honest and then we made it do exactly what we want. The name is both correct and clear.

But it is awkward.

We want to use this name to understand calling methods. It doesn’t yet serve that purpose. The name describes the thing. It doesn’t tell us why we care.

That makes us stumble when reading the caller. We want the names to tell us the purpose of each subcomponent. But right now the name tells us what it does—implementation when we want behavior/intent.

Every time we read a caller, we have to consider whether that implementation will give us our desired intent. That takes mental energy we could better spend elsewhere.

We’ve gotten as far as we can looking at our target to gain insights. Now we need to include the insights from its context.

Read through all the places where this thing is used. Understand it in the flow of other classes and method calls. What happens before, after, or with it?

Most likely the other names around this one will suck too. You need to improve them before you gain any insight. Sometimes insight will happen if the other parts are Honest, but you probably need to get to at least Completely Honest.

When you see all the context items at the Completely Honest level, you may realize that your target actually doesn’t Do the Right Thing. This is rare but it does happen. Fix it.

As you start to examine the use contexts you will start to see a flow. The target is one step in a larger orchestration. It has a purpose. That purpose is usually at a higher level of abstraction.

Rename the thing to state this purpose. Some common purposes are:

Methods:

- What it accomplishes (post-condition), regardless of starting state or process.

- Transformation it makes, regardless of beginning or ending states.

- Business process it replaces.

- Core responsibility the method takes on.

- What the method promises to allow callers to safely ignore.

Classes:

- The common responsibility of its methods.

- What the class is in the real world (Whole Value).

- The responsibility that calling context is delegating to the class and assuming the class will take care of. What the caller wants to ignore.

Variables:

- How this instance differs from other instances of the same type.

- The purpose the context has for this instance. How it is used.

In our running example, storeFlightToDatabaseAndShowOnScreenIfVisible(flight) becomes beginTrackingFlight(flight). The first name tells us what our method does. The second tells us why we care.

We don’t need to know what tracking a flight entails. We just need to know that this method will take care of initiating that process for us.

We would expect to see a stopTrackingFlight(flight) nearby. And perhaps some query methods to find information about flights that are being tracked.

Now repeat this step for another calling context. Your insight may be the same or your insightful name might be jarring in the other context. Often multiple callers are using the same code because of what it happens to do, not because of its purpose.

When this happens, create two methods that share an implementation. To the outside world, they are different things because they express different intents. It just happens that to a computer they do the same thing…for now.

Do the following:

- Extract method the entire body of the method.

- Rename the extracted (inner) method to the name you had that Does the Right Thing (which you can see in source history).

- Duplicate the outer method and edit its name to unique nonsense (do not refactor; you don’t want to update callers).

- Rename the unique nonsense to the new purpose.

- Edit the call site to use the method with the new purpose.

The reason we hand-edit to nonsense and then rename is so that our tool can catch errors. Hand-editing code is dangerous and something I tend to avoid.

I could duplicate a name or create aliasing problems, especially in the presence of inheritance or global functions with imported namespaces. But these are all problems that to rename refactoring checks for. By hand-editing to unique nonsense, I reduce the chance of making a mistake. And then renaming to the final name ensures that I don’t introduce one at that point.

For a class, the recipe depends on how your IDE does Split Class.

If Split Class supports delegation:

- Split Class and select everything. Choose the option to have all callers use the old type and create delegating members.

- Rename the inner type to the name you had after Doing the Right Thing.

- Copy the file for the outer type (assuming class-per-file).

- Hand-change the class name & constructors in the copied file to something guaranteed unique. Nonsense is good here.

- Rename the copied class to the new purpose.

- Update the construction site to instantiate the new class.

- Follow the compile errors, applying the auto-fix each time to change the type of the variable.

If Split Class doesn’t support delegation:

- Create a new class with a unique nonsense name, a single private field of the old type and constructors that match the old type. Use auto-generate members to create delegating members.

- Rename the old class back to its Does The Right Thing name to make sure that doesn’t cause conflicts.

- Undo the rename refactoring (it was just a test).

- Hand-edit the name of the outer class to the name the inner class has (the Intent name for the other context).

- Hand-edit the inner class to the Does the Right Thing name.

- Update the type and construction of the field in the outer class to use the correct type.

- At this point, all call sites will now be using the outer class via the purpose-based name.

- Pick up from step 3 in the recipe that assumed Split Class that supports delegation.

This recipe uses a common mini-recipe: introduce a new name for an extracted thing but leave all users using the outer thing.

If we can’t extract the inner thing, then we can get the same result by creating a new outer thing as a shim and then hand-editing the names (not updating the call site) to slip it into place.

It also uses a common refactoring test strategy. The most useful part of refactorings is not that they change your code, it is that they tell you what code changes are safe. Sometimes a refactoring won’t do exactly what you want, but you can still use its analysis to verify that the thing you want to do is safe.

We do and undo a rename refactoring to test whether our new names will create any conflicts, even though we execute the name changes by hand so that we can put the shim into place.

Naming by Intent is the easiest one to screw up. If you screw it up you will get a nonsense name. You won’t notice; the name will make sense to you right now because you have the full context. But it will be nonsense the next time you try to use it.

The problem is that this step is intentionally information-losing. We are replacing some of the information about what our thing does with information about why you care to use the thing. We are asking potential users to trust us. And we have to earn that trust. We earn it by using consistently clear names and code that Does the Right Things.

An extremely popular way to get nonsense is to name a thing by when it is used, rather than why it is used. This gets us right back to calling something preLoad(). One variation on this is to name a method by its initial condition. Ignore initial conditions in method names; they always end in broken abstractions.

Another popular route to nonsense is to create a new concept that is never used anywhere else. One-off abstractions are noise. Create your abstraction by looking at many named entities and use it uniformly.

But perhaps the most popular route to nonsense is to use a CS-y term. The domain of software engineering does not belong in your names unless you are writing a programming language. Even then, domain-specific languages are easier to read.

To avoid nonsense be specific about the context. Clearly state why someone would want to do the things that this class/method is doing. Keep any parts of the Complete and Honest name that make it more obvious when you want to use this thing. Drop the rest.

J. B. Rainsberger, “A Model for Improving Names”. This diagram summarizes how I think about gradually improving names over time.

J. B. Rainsberger, “Putting An Age-Old Battle To Rest”. In trying to settle the question of the relative importance of removing duplication and improving clarity, I describe how I believe these two mechanical techniques contribute to simplifying our designs.

Arlo Belshee, “Naming is a Process”. Another fantastic series of articles that describes a similar approach to names: improving names over time, rather than feeling stress to “get them right” “the first time”.

Katrina Owen, “What’s In a Name? Anti-Patterns to a Hard Problem”. An example along the path from nonsense through structural naming towards revealing intent, meaning, or purpose.

The two most terrible kinds of names are also the most common:

- Names that mislead you, and

- Important parts of something else, so they don’t even have a name.

In the spirit of naming as a process, we want a quick way to fix these two problems. It needs to be trivially fast and light, so that we can do it the hundreds of thousands of times that most codebases need.

Here the insights that I’m having are all the important characteristics of the thing I am naming. I’m naming it by what it does, not by what it is. This shift is a critical step in eliminating god classes and long methods.

- *Named by what it is…**When a thing is named by what it is, then it accumulates everything vaguely related to that identity. Use this when you want other coders to naturally gather related pieces of functionality from other code and increase cohesion.

- *Named by what it does…**When it is named by every single thing it does, then our desire for shorter names drives us to have it do less stuff. Use this when you want other coders to break it apart and simplify each chunk.

How something is named will drive the behavior of how people will engage with it and the future evolution of the method, variable, or class.

An extremely popular way to get nonsense is to name a thing by when it is used, rather than why it is used. This gets us right back to calling something preLoad(). One variation on this is to name a method by its initial condition. Ignore initial conditions in method names; they always end in broken abstractions.

Another popular route to nonsense is to create a new concept that is never used anywhere else. One-off abstractions are noise. Create your abstraction by looking at many named entities and use it uniformly.

But perhaps the most popular route to nonsense is to use a CS-y term. The domain of software engineering does not belong in your names unless you are writing a programming language. Even then, domain-specific languages are easier to read.

To avoid nonsense be specific about the context. Clearly state why someone would want to do the things that this class/method is doing. Keep any parts of the Complete and Honest name that make it more obvious when you want to use this thing. Drop the rest.